How JavaScript works: memory management + how to handle 4 common memory leaks

来源:互联网 发布:网络真人赌博软件开发 编辑:程序博客网 时间:2024/06/05 09:28

A few weeks ago we started a series aimed at digging deeper into JavaScript and how it actually works: we thought that by knowing the building blocks of JavaScript and how they come to play together you’ll be able to write better code and apps.

The first post of the series focused on providing an overview of the engine, the runtime, and the call stack. Thе second post examined closely the internal parts of Google’s V8 JavaScript engine and also provided a few tips on how to write better JavaScript code.

In this third post, we’ll discuss another critical topic that’s getting ever more neglected by developers due to the increasing maturity and complexity of programming languages that are being used on a daily basis — memory management. We’ll also provide a few tips on how to handle memory leaks in JavaScript that we at SessionStack follow as we need to make sure SessionStack causes no memory leaks or doesn’t increase the memory consumption of the web app in which we are integrated.

Overview

Languages, like C, have low-level memory management primitives such as malloc() and free(). These primitives are used by the developer to explicitly allocate and free memory from and to the operating system.

At the same time, JavaScript allocates memory when things (objects, strings, etc.) are created and “automatically” frees it up when they are not used anymore, a process called garbage collection. This seemingly “automatical” nature of freeing up resources is a source of confusion and gives JavaScript (and other high-level-language) developers the false impression they can choose not to care about memory management. This is a big mistake.

Even when working with high-level languages, developers should have an understanding of memory management (or at least the basics). Sometimes there are issues with the automatic memory management (such as bugs or implementation limitations in the garbage collectors, etc.) which developers have to understand in order to handle them properly (or to find a proper workaround, with a minimum trade off and code debt).

Memory life cycle

No matter what programming language you’re using, memory life cycle is pretty much always the same:

Here is an overview of what happens at each step of the cycle:

- Allocate memory — memory is allocated by the operating system which allows your program to use it. In low-level languages (e.g. C) this is an explicit operation that you as a developer should handle. In high-level languages, however, this is taken care of for you.

- Use memory — this is the time when your program actually makes use of the previously allocated memory. Read and write operations are taking place as you’re using the allocated variables in your code.

- Release memory — now is the time to release the entire memory that you don’t need so that it can become free and available again. As with the Allocate memory operation, this one is explicit in low-level languages.

For a quick overview of the concepts of the call stack and the memory heap, you can read our first post on the topic.

What is memory?

Before jumping straight to memory in JavaScript, we’ll briefly discuss what memory is in general and how it works in a nutshell.

On a hardware level, computer memory consists of a large number of

flip flops. Each flip flop contains a few transistors and is capable of storing one bit. Individual flip flops are addressable by a unique identifier, so we can read and overwrite them. Thus, conceptually, we can think of our entire computer memory as a just one giant array of bits that we can read and write.

Since as humans, we are not that good at doing all of our thinking and arithmetic in bits, we organize them into larger groups, which together can be used to represent numbers. 8 bits are called 1 byte. Beyond bytes, there are words (which are sometimes 16, sometimes 32 bits).

A lot of things are stored in this memory:

- All variables and other data used by all programs.

- The programs’ code, including the operating system’s.

The compiler and the operating system work together to take care of most of the memory management for you, but we recommend that you take a look at what’s going on under the hood.

When you compile your code, the compiler can examine primitive data types and calculate ahead of time how much memory they will need. The required amount is then allocated to the program in the call stack space. The space in which these variables are allocated is called the stack space because as functions get called, their memory gets added on top of the existing memory. As they terminate, they are removed in a LIFO (last-in, first-out) order. For example, consider the following declarations:

int n; // 4 bytesint x[4]; // array of 4 elements, each 4 bytesdouble m; // 8 bytes

The compiler can immediately see that the code requires

4 + 4 × 4 + 8 = 28 bytes.

That’s how it works with the current sizes for integers and doubles. About 20 years ago, integers were typically 2 bytes, and double 4 bytes. Your code should never have to depend on what is at this moment the size of the basic data types.

The compiler will insert code that will interact with the operating system to request the necessary number of bytes on the stack for your variables to be stored.

In the example above, the compiler knows the exact memory address of each variable. In fact, whenever we write to the variable n, this gets translated into something like “memory address 4127963” internally.

Notice that if we attempted to access x[4] here, we would have accessed the data associated with m . That’s because we’re accessing an element in the array that doesn’t exist — it’s 4 bytes further than the last actual allocated element in the array which is x[3], and may end up reading (or overwriting) some of m’s bits. This would almost certainly have very undesired consequences for the rest of the program.

When functions call other functions, each gets its own chunk of the stack when it is called. It keeps all its local variables there, but also a program counter that remembers where in its execution it was. When the function finishes, its memory block is once again made available for other purposes.

Dynamic allocation

Unfortunately, things aren’t quite as easy when we don’t know at compile time how much memory a variable will need. Suppose we want to do something like the following:

int n = readInput(); // reads input from the user

...

// create an array with "n" elements

Here, at compile time, the compiler does not know how much memory the array will need because it is determined by the value provided by the user.

It, therefore, cannot allocate room for a variable on the stack. Instead, our program needs to explicitly ask the operating system for the right amount of space at run-time. This memory is assigned from the heap space. The difference between static and dynamic memory allocation is summarized in the following table:

To fully understand how dynamic memory allocation works, we need to spend more time on pointers, which might be a bit too much of a deviation from the topic of this post. If you’re interested in learning more, just let me know in the comments and we can go into more details about pointers in a future post.

Allocation in JavaScript

Now we’ll explain how the first step (allocate memory) works in JavaScript.

JavaScript relieves developers from the responsibility to handle memory allocations — JavaScript does it by itself, alongside declaring values.

var n = 374; // allocates memory for a numbervar s = 'sessionstack'; // allocates memory for a string var o = { a: 1, b: null}; // allocates memory for an object and its contained valuesvar a = [1, null, 'str']; // (like object) allocates memory for the // array and its contained valuesfunction f(a) { return a + 3;} // allocates a function (which is a callable object)// function expressions also allocate an objectsomeElement.addEventListener('click', function() { someElement.style.backgroundColor = 'blue';}, false);Some function calls result in object allocation as well:

var d = new Date(); // allocates a Date objectvar e = document.createElement('div'); // allocates a DOM elementMethods can allocate new values or objects:

var s1 = 'sessionstack';var s2 = s1.substr(0, 3); // s2 is a new string// Since strings are immutable, // JavaScript may decide to not allocate memory, // but just store the [0, 3] range.var a1 = ['str1', 'str2'];var a2 = ['str3', 'str4'];var a3 = a1.concat(a2); // new array with 4 elements being// the concatenation of a1 and a2 elementsUsing memory in JavaScript

Using the allocated memory in JavaScript basically, means reading and writing in it.

This can be done by reading or writing the value of a variable or an object property or even passing an argument to a function.

Release when the memory is not needed anymore

Most of the memory management issues come at this stage.

The hardest task here is to figure out when the allocated memory is not needed any longer. It often requires the developer to determine where in the program such piece of memory is not needed anymore and free it.

High-level languages embed a piece of software called garbage collectorwhich job is to track memory allocation and use in order to find when a piece of allocated memory is not needed any longer in which case, it will automatically free it.

Unfortunately, this process is an approximation since the general problem of knowing whether some piece of memory is needed is undecidable (can’t be solved by an algorithm).

Most garbage collectors work by collecting memory which can no longer be accessed, e.g. all variables pointing to it went out of scope. That’s, however, an under-approximation of the set of memory spaces that can be collected, because at any point a memory location may still have a variable pointing to it in scope, yet it will never be accessed again.

Garbage collection

Due to the fact that finding whether some memory is “not needed anymore” is undecidable, garbage collections implement a restriction of a solution to the general problem. This section will explain the necessary notions to understand the main garbage collection algorithms and their limitations.

Memory references

The main concept garbage collection algorithms rely on is the one of reference.

Within the context of memory management, an object is said to reference another object if the former has an access to the latter (can be implicit or explicit). For instance, a JavaScript object has a reference to its prototype(implicit reference) and to its properties’ values (explicit reference).

In this context, the idea of an “object” is extended to something broader than regular JavaScript objects and also contains function scopes (or the global lexical scope).

Lexical Scoping defines how variable names are resolved in nested functions: inner functions contain the scope of parent functions even if the parent function has returned.

Reference-counting garbage collection

This is the simplest garbage collection algorithm. An object is considered “garbage collectible” if there are zero references pointing to it.

Take a look at the following code:

var o1 = { o2: { x: 1 }};// 2 objects are created. // 'o2' is referenced by 'o1' object as one of its properties.// None can be garbage-collectedvar o3 = o1; // the 'o3' variable is the second thing that // has a reference to the object pointed by 'o1'. o1 = 1; // now, the object that was originally in 'o1' has a // single reference, embodied by the 'o3' variablevar o4 = o3.o2; // reference to 'o2' property of the object. // This object has now 2 references: one as // a property. // The other as the 'o4' variableo3 = '374'; // The object that was originally in 'o1' has now zero // references to it. // It can be garbage-collected. // However, what was its 'o2' property is still // referenced by the 'o4' variable, so it cannot be // freed.o4 = null; // what was the 'o2' property of the object originally in // 'o1' has zero references to it. // It can be garbage collected.Cycles are creating problems

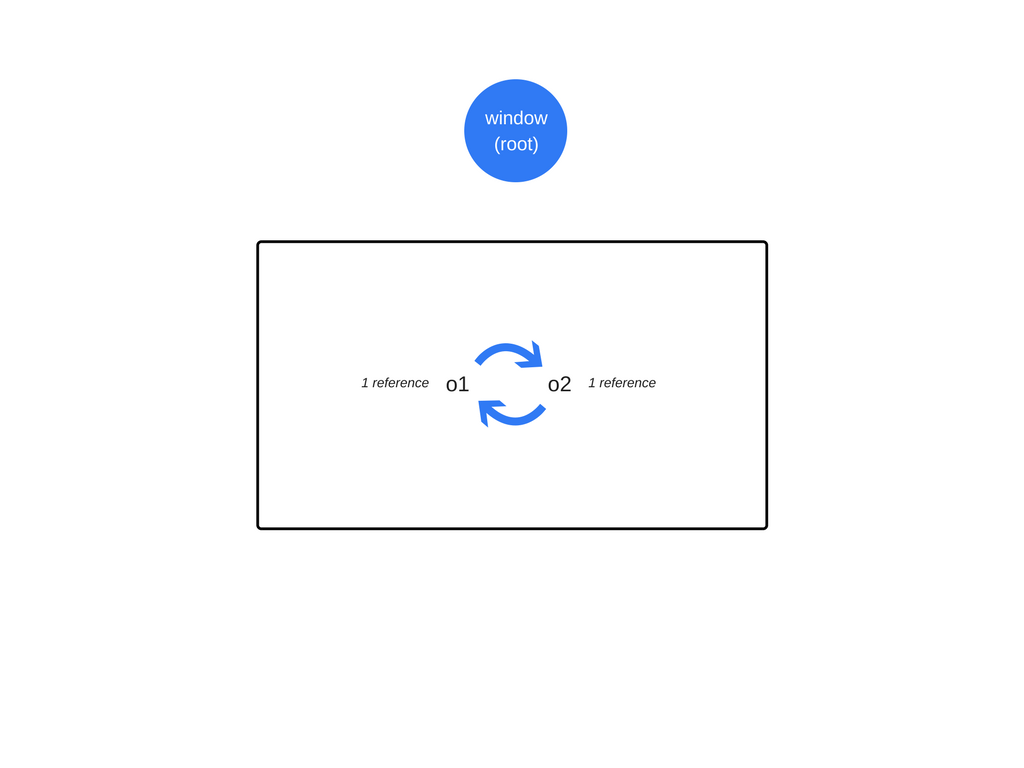

There is a limitation when it comes to cycles. In the following example, two objects are created and reference one another, thus creating a cycle. They will go out of scope after the function call, so they are effectively useless and could be freed. However, the reference-counting algorithm considers that since each of the two objects is referenced at least once, neither can be garbage-collected.

function f() { var o1 = {}; var o2 = {}; o1.p = o2; // o1 references o2 o2.p = o1; // o2 references o1. This creates a cycle.}f();

Mark-and-sweep algorithm

In order to decide whether an object is needed, this algorithm determines whether the object is reachable.

The algorithm consists of the following steps:

- The garbage collector builds a list of “roots”. Roots usually are global variables to which a reference is kept in the code. In JavaScript, the “window” object is an example of a global variable that can act as a root.

- All roots are inspected and marked as active (i.e. not garbage). All children are inspected recursively as well. Everything that can be reached from a root is not considered garbage.

- All pieces of memory not marked as active can now be considered garbage. The collector can now free that memory and return it to the OS.

This algorithm is better than the previous one since “an object has zero reference” leads to this object being unreachable. The opposite is not true as we have seen with cycles.

As of 2012, all modern browsers ship a mark-and-sweep garbage-collector. All improvements made in the field of JavaScript garbage collection (generational/incremental/concurrent/parallel garbage collection) over the last years are implementation improvements of this algorithm (mark-and-sweep), but not improvements over the garbage collection algorithm itself, nor its goal of deciding whether an object is reachable or not.

In this article, you can read in a greater detail about tracing garbage collection that also covers mark-and-sweep along with its optimizations.

Cycles are not a problem anymore

In the first example above, after the function call returns, the two objects are not referenced anymore by something reachable from the global object. Consequently, they will be found unreachable by the garbage collector.

Even though there are references between the objects, they’re not reachable from the root.

Counter intuitive behavior of Garbage Collectors

Although Garbage Collectors are convenient they come with their own set of trade-offs. One of them is non-determinism. In other words, GCs are unpredictable. You can’t really tell when a collection will be performed. This means that in some cases programs use more memory that it’s actually required. In other cases, short-pauses may be noticeable in particularly sensitive applications. Although non-determinism means one cannot be certain when a collection will be performed, most GC implementations share the common pattern of doing collection passes during allocation. If no allocations are performed, most GCs stay idle. Consider the following scenario:

- A sizable set of allocations is performed.

- Most of these elements (or all of them) are marked as unreachable (suppose we null a reference pointing to a cache we no longer need).

- No further allocations are performed.

In this scenario, most GCs will not run any further collection passes. In other words, even though there are unreachable references available for collection, these are not claimed by the collector. These are not strictly leaks but still, result in higher-than-usual memory usage.

What are memory leaks?

In essence, memory leaks can be defined as memory that is not required by the application anymore but for some reason is not returned to the operating system or the pool of free memory.

Programming languages favor different ways of managing memory. However, whether a certain piece of memory is used or not is actually an undecidable problem. In other words, only developers can make it clear whether a piece of memory can be returned to the operating system or not.

Certain programming languages provide features that help developers do this. Others expect developers to be completely explicit about when a piece of memory is unused. Wikipedia has good articles on manual and automaticmemory management.

The four types of common JavaScript leaks

1: Global variables

JavaScript handles undeclared variables in an interesting way: a reference to an undeclared variable creates a new variable inside the global object. In the case of browsers, the global object is window. In other words:

function foo(arg) { bar = "some text";}is the equivalent of:

function foo(arg) { window.bar = "some text";}If bar was supposed to hold a reference to a variable only inside the scope of the foo function and you forget to use var to declare it, an unexpected global variable is created.

In this example, leaking a simple string won't do much harm, but it could certainly be worse.

Another way in which an accidental global variable can be created is through this:

function foo() { this.var1 = "potential accidental global";}// Foo called on its own, this points to the global object (window)// rather than being undefined.foo();To prevent these mistakes from happening, add 'use strict'; at the beginning of your JavaScript files. This enables a stricter mode of parsing JavaScript that prevents accidental global variables. Learn more about this mode of JavaScript execution.Even though we talk about unsuspected globals, it’s still the case that much code is filled with explicit global variables. These are by definition non-collectible (unless assigned as null or reassigned). In particular, global variables that are used to temporarily store and process big amounts of information are of concern. If you must use a global variable to store lots of data, make sure to assign it as null or reassign it after you are done with it.

2: Timers or callbacks that are forgotten

The use of setInterval is quite common in JavaScript.

Most libraries, that provide observers and other facilities that take callbacks, take care of making any references to the callback unreachable after their own instances become unreachable as well. In the case of setInterval, however, code like this is quite common:

var serverData = loadData();setInterval(function() { var renderer = document.getElementById('renderer'); if(renderer) { renderer.innerHTML = JSON.stringify(serverData); }}, 5000); //This will be executed every ~5 seconds.This example illustrates what can happen with timers: timers that make reference to nodes or data that is no longer required.

The object represented by renderer may be removed in the future, making the whole block inside the interval handler unnecessary. However, the handler cannot be collected as the interval is still active, (the interval needs to be stopped for this to happen). If the interval handler cannot be collected, its dependencies cannot be collected either. This means that serverData, which presumably stores quite a big amount of data, cannot be collected either.

In the case of observers, it is important to make explicit calls to remove them once they are not needed anymore (or the associated object is about to be made unreachable).

In the past, this used to be particularly important as certain browsers (the good old IE 6) were not able to manage well cyclic references (see below for more info). Nowadays, most browsers can and will collect observer handlers once the observed object becomes unreachable, even if the listener is not explicitly removed. It remains good practice, however, to explicitly remove these observers before the object is disposed of. For instance:

var element = document.getElementById('launch-button');var counter = 0;function onClick(event) { counter++; element.innerHtml = 'text ' + counter;}element.addEventListener('click', onClick);// Do stuffelement.removeEventListener('click', onClick);element.parentNode.removeChild(element);// Now when element goes out of scope,// both element and onClick will be collected even in old browsers // that don't handle cycles well.Nowadays, modern browsers (including Internet Explorer and Microsoft Edge) use modern garbage collection algorithms that can detect these cycles and deal with them correctly. In other words, it’s not strictly necessary to call removeEventListener before making a node unreachable.

Frameworks and libraries such as jQuery do remove listeners before disposing of a node (when using their specific APIs for that). This is handled internally by the libraries which also make sure that no leaks are produced, even when running under problematic browsers such as … yeah, IE 6.

3: Closures

A key aspect of JavaScript development are closures: an inner function that has access to the outer (enclosing) function’s variables. Due to the implementation details of the JavaScript runtime, it is possible to leak memory in the following way:

var theThing = null;

var replaceThing = function () { var originalThing = theThing; var unused = function () { if (originalThing) // a reference to 'originalThing' console.log("hi"); }; theThing = { longStr: new Array(1000000).join('*'), someMethod: function () { console.log("message"); } };};setInterval(replaceThing, 1000);

This snippet does one thing: every time replaceThing is called, theThing gets a new object which contains a big array and a new closure (someMethod). At the same time, the variable unused holds a closure that has a reference to originalThing (theThing from the previous call to replaceThing). Already somewhat confusing, huh? The important thing is that once a scope is created for closures that are in the same parent scope, that scope is shared.

In this case, the scope created for the closure someMethod is shared with unused. unused has a reference to originalThing. Even though unused is never used, someMethod can be used through theThing outside of the scope of replaceThing (e.g. somewhere globally). And as someMethod shares the closure scope with unused, the reference unused has to originalThing forces it to stay active (the whole shared scope between the two closures). This prevents its collection.

When this snippet is run repeatedly a steady increase in memory usage can be observed. This does not get smaller when the GC runs. In essence, a linked list of closures is created (with its root in the form of the theThing variable), and each of these closures' scopes carries an indirect reference to the big array, resulting in a sizable leak.

This issue was found by the Meteor team and they have a great article that describes the issue in great detail.

4: Out of DOM references

Sometimes it may be useful to store DOM nodes inside data structures. Suppose you want to rapidly update the contents of several rows in a table. It may make sense to store a reference to each DOM row in a dictionary or an array. When this happens, two references to the same DOM element are kept: one in the DOM tree and the other in the dictionary. If at some point in the future you decide to remove these rows, you need to make both references unreachable.

var elements = { button: document.getElementById('button'), image: document.getElementById('image')};function doStuff() { elements.image.src = 'http://example.com/image_name.png';}function removeImage() { // The image is a direct child of the body element. document.body.removeChild(document.getElementById('image')); // At this point, we still have a reference to #button in the //global elements object. In other words, the button element is //still in memory and cannot be collected by the GC.}There’s an additional consideration that has to be taken into account when it comes to references to inner or leaf nodes inside a DOM tree. Say you keep a reference to a specific cell of a table (a <td> tag) in your JavaScript code. One day you decide to remove the table from the DOM but keep the reference to that cell. Intuitively one may suppose the GC will collect everything but that cell. In reality, this won’t happen: the cell is a child node of that table and children keep references to their parents. That is, the reference to the table cell from JavaScript code causes the whole table to stay in memory. Consider this carefully when keeping references to DOM elements.

We at SessionStack try to follow these best practices in writing code that handles memory allocation properly, and here’s why:

Once you integrate SessionStack into your production web app, it starts recording everything: all DOM changes, user interactions, JavaScript exceptions, stack traces, failed network requests, debug messages, etc.

With SessionStack, you replay issues in your web apps as videos and see everything that happened to your user. And all of this has to take place with no performance impact for your web app.

Since the user can reload the page or navigate your app, all observers, interceptors, variable allocations, etc. have to be handled properly, so they don’t cause any memory leaks or don’t increase the memory consumption of the web app in which we are integrated.

There is a free plan so you can give it a try now.

Resources

- http://www-bcf.usc.edu/~dkempe/CS104/08-29.pdf

- https://blog.meteor.com/an-interesting-kind-of-javascript-memory-leak-8b47d2e7f156

- http://www.nodesimplified.com/2017/08/javascript-memory-management-and.html

- How JavaScript works: memory management + how to handle 4 common memory leaks

- How to Fix Memory Leaks in Java

- How Virtual Memory Works

- Memory leaks in C++ and how to avoid them

- How To Debug Memory Leaks with XCode and Instruments Tutorial

- How to avoid memory leaks in iPhone applications

- How to check memory leaks in android app?

- How to handle various of Out Of Memory Issues

- How to handle various of Out Of Memory Issues

- memory:How Memory Works: 10 Things Most People Get Wrong

- Umdhtools.exe: How to Use Umdh.exe to Find Memory Leaks

- DM6467 memory map HOW-TO

- DM6467 memory map HOW-TO

- How to troubleshoot memory problems

- how to debug memory-leak

- [iOS开发站在巨人肩膀上]之How to avoid memory leaks in iPhone applications

- How to detect and avoid memory and resources leaks in .NET applications()

- How To Debug Memory Leaks with XCode and Instruments Tutorial 边读边记

- react 实战案例(webpack构建)

- Go的http包详解

- linux基础

- Java导出Excel和图片

- 二叉排序树、平衡树、红黑树

- How JavaScript works: memory management + how to handle 4 common memory leaks

- karto_slam 框架

- PHP中get_magic_quotes_gpc()函数是内置的函数,这个函数的作用就是得到php.ini设置中magic_quotes_gpc选项的值。

- poj1204Word Puzzles,caioj1465地图匹配(AC自动机+搜索)

- The Tower of Babalon,Uva 437(有向图的DAG)

- OSGI框架下,bundle的两种启动方式

- 一起艳学大数据Hadoop(二)——eclipse配置hadoop

- 第三周项目3---求集合并集

- redis长连接的原理和示例