浏览器的工作原理:新式网络浏览器幕后揭秘{转}

来源:互联网 发布:软件项目建议书模板 编辑:程序博客网 时间:2024/05/18 06:23

//我是 "转"的~这么大牛的文章, 我会慢慢理解和回味~

http://taligarsiel.com/Projects/howbrowserswork1.htm

http://www.html5rocks.com/zh/tutorials/internals/howbrowserswork/

浏览器的渲染原理简介

- Introduction

- The browsers we will talk about

- The browser's main functionality

- The browser's high level structure

- Communication_between the components

- The rendering engine

- Rendering engines

- The main flow

- Main flow examples

- Parsing and DOM tree construction

- Parsing - general

- Grammars

- Parser - Lexer combination

- Translation

- Parsing example

- Formal definitions for vocabulary and syntax

- Types of parsers

- Generating parsers automatically

- HTML Parser

- The HTML grammar definition

- Not a context free grammar

- HTML DTD

- DOM

- The parsing algorithm

- The tokenization algorithm

- Tree construction algorithm

- Actions when the parsing is finished

- Browsers error tolerance

- CSS parsing

- Webkit CSS parser

- Parsing scripts

- The order of processing scripts and style sheets

- Scripts

- Speculative parsing

- Style sheets

- Parsing - general

- Render tree construction

- The render tree relation to the DOM tree

- The flow of constructing the tree

- Style Computation

- Sharing style data

- Firefox rule tree

- Division into structs

- Computing the style contexts using the rule tree

- Manipulating the rules for an easy match

- Applying the rules in the correct cascade order

- Style sheet cascade order

- Specifity

- Sorting the rules

- Gradual process

- Layout

- Dirty bit system

- Global and incremental layout

- Asynchronous and Synchronous layout

- Optimizations

- The layout process

- Width calculation

- Line Breaking

- Painting

- Global and Incremental

- The painting order

- Firefox display list

- Webkit rectangle storage

- Dynamic changes

- The rendering engine's threads

- Event loop

- CSS2 visual model

- The canvas

- CSS Box model

- Positioning scheme

- Box types

- Positioning

- Relative

- Floats

- Absolute and fixed

- Layered representation

- Resources

Introduction

Web browsers are probably the most widely used software. In this book I will explain how they work behind the scenes. We will see what happens when you type 'google.com' in the address bar until you see the Google page on the browser screen.

The browsers we will talk about

There are five major browsers used today - Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, Chrome and Opera.

I will give examples from the open source browsers - Firefox,Chrome and Safari, which is partly open source.

According to the W3C browser statistics, currently(October 2009), the usage share of Firefox, Safari and Chrome together is nearly 60%.

So nowdays open source browsers are a substantial part of the browser business.

The browser's main functionality

The browser main functionality is to present the web resource you choose, by requesting it from the server and displaying it on the browser window. The resource format is usually HTML but also PDF, image and more. The location of the resource is specified by the user using a URI (Uniform resource Identifier). More on that in the network chapter.

The way the browser interprets and displays HTML files is specified in the HTML and CSS specifications. These specifications are maintained by the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) organization, which is the standards organization for the web.

The current version of HTML is 4 (http://www.w3.org/TR/html401/). Version 5 is in progress. The current CSS version is 2 (http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/) and version 3 is in progress.

For years browsers conformed to only a part of the specifications and developed their own extensions. That caused serious compatibility issues for web authors. Today most of the browsers more or less conform to the specifications.

Browsers' user interface have a lot in common with each other. Among the common user interface elements are:

- Address bar for inserting the URI

- Back and forward buttons

- Bookmarking options

- A refresh and stop buttons for refreshing and stopping the loading of current documents

- Home button that gets you to your home page

More on that in the user interface chapter.

The browser's high level structure

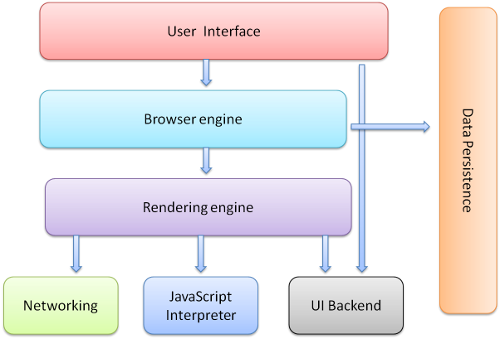

The browser's main components are (1.1):

- The user interface - this includes the address bar, back/forward button, bookmarking menu etc. Every part of the browser display except the main window where you see the requested page.

- The browser engine - the interface for querying and manipulating the rendering engine.

- The rendering engine - responsible for displaying the requested content. For example if the requested content is HTML, it is responsible for parsing the HTML and CSS and displaying the parsed content on the screen.

- Networking - used for network calls, like HTTP requests. It has platform independent interface and underneath implementations for each platform.

- UI backend - used for drawing basic widgets like combo boxes and windows. It exposes a generic interface that is not platform specific. Underneath it uses the operating system user interface methods.

- JavaScript interpreter. Used to parse and execute the JavaScript code.

- Data storage. This is a persistence layer. The browser needs to save all sorts of data on the hard disk, for examples, cookies. The new HTML specification (HTML5) defines 'web database' which is a complete (although light) database in the browser.

Figure 1: Browser main components.

It is important to note that Chrome, unlike most browsers, holds multiple instances of the rendering engine - one for each tab,. Each tab is a separate process.

I will devote a chapter for each of these components.

Communication between the components

Both Firefox and Chrome developed a special communication infrastructures.

They will be discussed in a special chapter.

The rendering engine

The responsibility of the rendering engine is well... Rendering, that is display of the requested contents on the browser screen.

By default the rendering engine can display HTML and XML documents and images. It can display other types through a plug-in (a browser extension). An example is displaying PDF using a PDF viewer plug-in. We will talk about plug-ins and extensions in a special chapter. In this chapter we will focus on the main use case - displaying HTML and images that are formatted using CSS.

Rendering engines

Our reference browsers - Firefox, Chrome and Safari are built upon two rendering engines. Firefox uses Gecko - a "home made" Mozilla rendering engine. Both Safari and Chrome use Webkit.

Webkit is an open source rendering engine which started as an engine for the Linux platform and was modified by Apple to support Mac and Windows. See http://webkit.org/ for more details.

The main flow

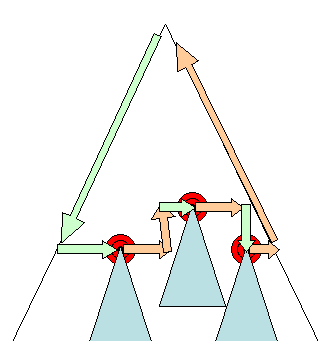

The rendering engine will start getting the contents of the requested document from the networking layer. This will usually be done in 8K chunks.

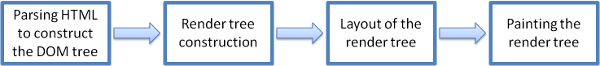

After that this is the basic flow of the rendering engine:

Figure 2:Rendering engine basic flow.

The rendering engine will start parsing the HTML document and turn the tags to DOM nodes in a tree called the "content tree". It will parse the style data, both in external CSS files and in style elements. The styling information together with visual instructions in the HTML will be used to create another tree - the render tree.

The render tree contains rectangles with visual attributes like color and dimensions. The rectangles are in the right order to be displayed on the screen.

After the construction of the render tree it goes through a "layout" process. This means giving each node the exact coordinates where it should appear on the screen. The next stage is painting - the render tree will be traversed and each node will be painted using the UI backend layer.

It's important to understand that this is a gradual process. For better user experience, the rendering engine will try to display contents on the screen as soon as possible. It will not wait until all HTML is parsed before starting to build and layout the render tree. Parts of the content will be parsed and displayed, while the process continues with the rest of the contents that keeps coming from the network.

Main flow examples

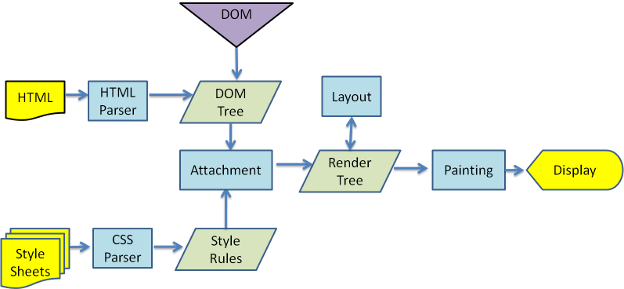

Figure 3: Webkit main flow

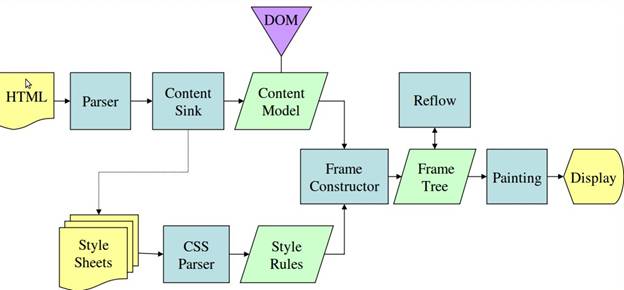

Figure 4: Mozilla's Gecko rendering engine main flow(3.6)

From figures 3 and 4 you can see that although Webkit and Gecko use slightly different terminology, the flow is basically the same.

Gecko calls the tree of visually formatted elements - Frame tree. Each element is a frame. Webkit uses the term "Render Tree" and it consists of "Render Objects". Webkit uses the term "layout" for the placing of elements, while Gecko calls it "Reflow". "Attachment" is Webkit's term for connecting DOM nodes and visual information to create the render tree. A minor non semantic difference is that Gecko has an extra layer between the HTML and the DOM tree. It is called the "content sink" and is a factory for making DOM elements. We will talk about each part of the flow:

Parsing - general

Since parsing is a very significant process within the rendering engine, we will go into it a little more deeply. Let's begin with a little introduction about parsing.

Parsing a document means translating it to some structure that makes sense - something the code can understand and use. The result of parsing is usually a tree of nodes that represent the structure of the document. It is called a parse tree or a syntax tree.

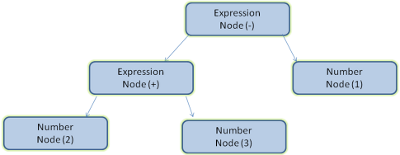

Example - parsing the expression "2 + 3 - 1" could return this tree:

Figure 5: mathematical expression tree node

Grammars

Parsing is based on the syntax rules the document obeys - the language or format it was written in. Every format you can parse must have deterministic grammar consisting of vocabulary and syntax rules. It is called a context free grammar. Human languages are not such languages and therefore cannot be parsed with conventional parsing techniques.

Parser - Lexer combination

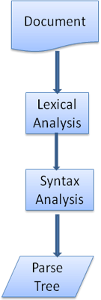

Parsing can be separated into two sub processes - lexical analysis and syntax analysis.

Lexical analysis is the process of breaking the input into tokens. Tokens are the language vocabulary - the collection of valid building blocks. In human language it will consist of all the words that appear in the dictionary for that language.

Syntax analysis is the applying of the language syntax rules.

Parsers usually divide the work between two components - the lexer(sometimes called tokenizer) that is responsible for breaking the input into valid tokens, and the parser that is responsible for constructing the parse tree by analyzing the document structure according to the language syntax rules. The lexer knows how to strip irrelevant characters like white spaces and line breaks.

Figure 6: from source document to parse trees

The parsing process is iterative. The parser will usually ask the lexer for a new token and try to match the token with one of the syntax rules. If a rule is matched, a node corresponding to the token will be added to the parse tree and the parser will ask for another token.

If no rule matches, the parser will store the token internally, and keep asking for tokens until a rule matching all the internally stored tokens is found. If no rule is found then the parser will raise an exception. This means the document was not valid and contained syntax errors.

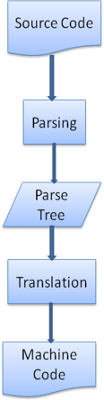

Translation

Many times the parse tree is not the final product. Parsing is often used in translation - transforming the input document to another format. An example is compilation. The compiler that compiles a source code into machine code first parses it into a parse tree and then translates the tree into a machine code document.

Figure 7: compilation flow

Parsing example

In figure 5 we built a parse tree from a mathematical expression. Let's try to define a simple mathematical language and see the parse process.

Vocabulary: Our language can include integers, plus signs and minus signs.

Syntax:

- The language syntax building blocks are expressions, terms and operations.

- Our language can include any number of expressions.

- A expression is defined as a "term" followed by an "operation" followed by another term

- An operation is a plus token or a minus token

- A term is an integer token or an expression

Let's analyze the input "2 + 3 - 1".

The first substring that matches a rule is "2", according to rule #5 it is a term. The second match is "2 + 3" this matches the second rule - a term followed by an operation followed by another term. The next match will only be hit at the end of the input. "2 + 3 - 1" is an expression because we already know that ?2+3? is a term so we have a term followed by an operation followed by another term. "2 + + "will not match any rule and therefore is an invalid input.

Formal definitions for vocabulary and syntax

Vocabulary is usually expressed by regular expressions.

For example our language will be defined as:

INTEGER :0|[1-9][0-9]*PLUS : +MINUS: -As you see, integers are defined by a regular expression.

Syntax is usually defined in a format called BNF. Our language will be defined as:

expression := term operation termoperation := PLUS | MINUSterm := INTEGER | expression

We said that a language can be parsed by regular parsers if its grammar is a context frees grammar. An intuitive definition of a context free grammar is a grammar that can be entirely expressed in BNF. For a formal definition seehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Context-free_grammar

Types of parsers

There are two basic types of parsers - top down parsers and bottom up parsers. An intuitive explanation is that top down parsers see the high level structure of the syntax and try to match one of them. Bottom up parsers start with the input and gradually transform it into the syntax rules, starting from the low level rules until high level rules are met.

Let's see how the two types of parsers will parse our example:

Top down parser will start from the higher level rule - it will identify "2 + 3" as an expression. It will then identify "2 + 3 - 1" as an expression (the process of identifying the expression evolves matching the other rules, but the start point is the highest level rule).

The bottom up parser will scan the input until a rule is matched it will then replace the matching input with the rule. This will go on until the end of the input. The partly matched expression is placed on the parsers stack.

This type of bottom up parser is called a shift reduce parser, because the input is shifted to the right (imagine a pointer pointing first at the input start and moving to the right) and is gradually reduced to syntax rules.

Generating parsers automatically

There are tools that can generate a parser for you. They are called parser generators. You feed them with the grammar of your language - its vocabulary and syntax rules and they generate a working parser. Creating a parser requires a deep understanding of parsing and its not easy to create an optimized parser by hand, so parser generators can be very useful.

Webkit uses two well known parser generators - Flex for creating a lexer and Bison for creating a parser (you might run into them with the names Lex and Yacc). Flex input is a file containing regular expression definitions of the tokens. Bison's input is the language syntax rules in BNF format.

HTML Parser

The job of the HTML parser is to parse the HTML markup into a parse tree.

The HTML grammar definition

The vocabulary and syntax of HTML are defined in specifications created by the w3c organization. The current version is HTML4 and work on HTML5 is in progress.

Not a context free grammar

As we have seen in the parsing introduction, grammar syntax can be defined formally using formats like BNF.

Unfortunately all the conventional parser topics do not apply to HTML (I didn't bring them up just for fun - they will be used in parsing CSS and JavaScript). HTML cannot easily be defined by a context free grammar that parsers need.

There is a formal format for defining HTML - DTD (Document Type Definition) - but it is not a context free grammar.

This appears strange at first site - HTML is rather close to XML .There are lots of available XML parsers. There is an XML variation of HTML - XHTML - so what's the big difference?

The difference is that HTML approach is more "forgiving", it lets you omit certain tags which are added implicitly, sometimes omit the start or end of tags etc. On the whole it's a "soft" syntax, as opposed to XML's stiff and demanding syntax.

Apparently this seemingly small difference makes a world of a difference. On one hand this is the main reason why HTML is so popular - it forgives your mistakes and makes life easy for the web author. On the other hand, it makes it difficult to write a format grammar. So to summarize - HTML cannot be parsed easily, not by conventional parsers since its grammar is not a context free grammar, and not by XML parsers.

HTML DTD

HTML definition is in a DTD format. This format is used to define languages of the SGML family. The format contains definitions for all allowed elements, their attributes and hierarchy. As we saw earlier, the HTML DTD doesn't form a context free grammar.

There are a few variations of the DTD. The strict mode conforms solely to the specifications but other modes contain support for markup used by browsers in the past. The purpose is backwards compatibility with older content. The current strict DTD is here:http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd

DOM

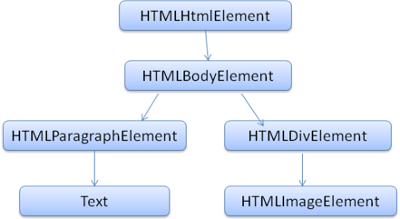

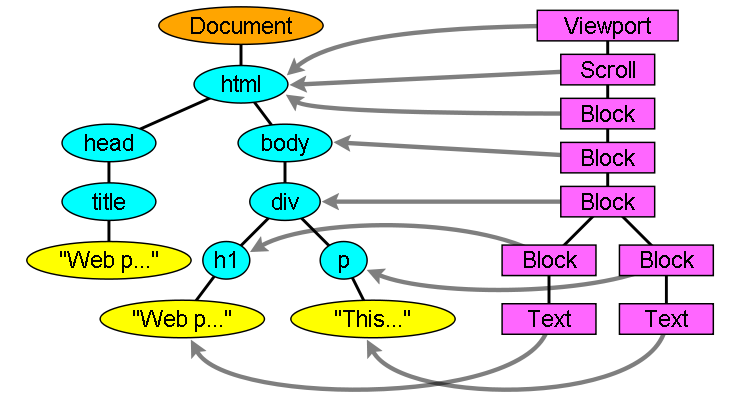

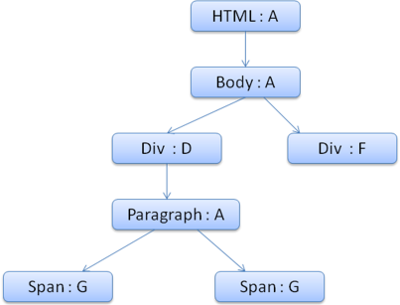

The output tree - the parse tree is a tree of DOM element and attribute nodes. DOM is short for Document Object Model. It is the object presentation of the HTML document and the interface of HTML elements to the outside world like JavaScript.

The root of the tree is the "Document" object.

The DOM has an almost one to one relation to the markup. Example, this markup:

<html><body><p>Hello World</p><div> <img src="example.png"/></div></body></html>Would be translated to the following DOM tree:

Figure 8: DOM tree of the example markup

Like HTML, DOM is specified by the w3c organization. See http://www.w3.org/DOM/DOMTR. It is a generic specification for manipulating documents. A specific module describes HTML specific elements. The HTML definitions can be found here:http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-DOM-Level-2-HTML-20030109/idl-definitions.html.

When I say the tree contains DOM nodes, I mean the tree is constructed of elements that implement one of the DOM interfaces. Browsers use concrete implementations that have other attributes used by the browser internally.

The parsing algorithm

As we saw in the previous sections, HTML cannot be parsed using the regular top down or bottom up parsers.

The reasons are:

- The forgiving nature of the language.

- The fact that browsers have traditional error tolerance to support well known cases of invalid HTML.

- The parsing process in reentrant. Usually the source doesn't change during parsing, but in HTML, script tags containing "document.write" can add extra tokens, so the parsing process actually modifies the input.

Unable to use the regular parsing techniques, browsers create custom parsers for parsing HTML.

The parsing algorithm is described in details by the HTML5 specification. The algorithm consists of two stages - tokenization and tree construction.

Tokenization is the lexical analysis, parsing the input into tokens. Among HTML tokens are start tags, end tags, attribute names and attribute values.

The tokenizer recognizes the token, gives it to the tree constructor and consumes the next character for recognizing the next token and so on until the end of the input.

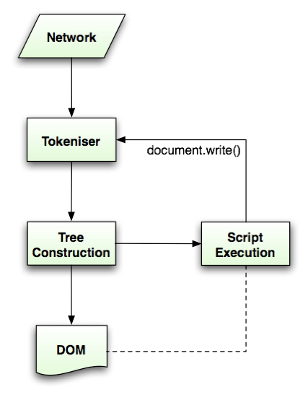

Figure 6: HTML parsing flow (taken from HTML5 spec)

The tokenization algorithm

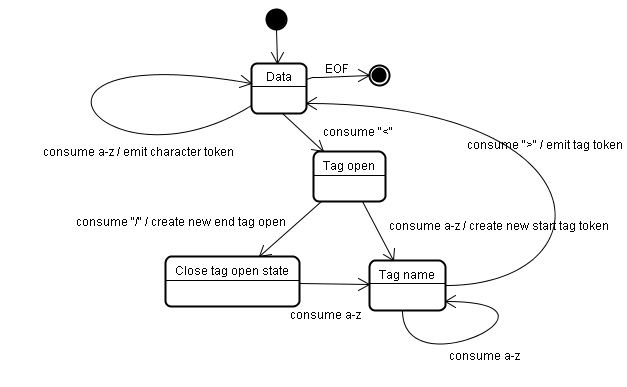

The algorithm's output is an HTML token. The algorithm is expressed as a state machine. Each state consumes one or more characters of the input stream and updates the next state according to those characters. The decision is influenced by the current tokenization state and by the tree construction state. This means the same consumed character will yield different results for the correct next state, depending on the current state. The algorithm is too complex to bring fully, so let's see a simple example that will help us understand the principal.

Basic example - tokenizing the following HTML:

<html><body>Hello world</body></html>The initial state is the "Data state". When the "<" character is encountered, the state is changed to "Tag open state". Consuming an "a-z" character causes creation of a "Start tag token", the state is change to "Tag name state". We stay in this state until the ">" character is consumed. Each character is appended to the new token name. In our case the created token is an "html" token.

When the ">" tag is reached, the current token is emitted and the state changes back to the "Data state". The "<body>" tag will be treated by the same steps. So far the "html" and "body" tags were emitted. We are now back at the "Data state". Consuming the "H" character of "Hello world" will cause creation and emitting of a character token, this goes on until the "<" of "</body>" is reached. We will emit a character token for each character of "Hello world".

We are now back at the "Tag open state". Consuming the next input "/" will cause creation of an "end tag token" and a move to the "Tag name state". Again we stay in this state until we reach ">".Then the new tag token will be emitted and we go back to the"Data state". The "</html>" input will be treated like the previous case.

Figure 9: Tokenizing the example input

Tree construction algorithm

When the parser is created the Document object is created. During the tree construction stage the DOM tree with the Document in its root will be modified and elements will be added to it. Each node emitted by the tokenizer will be processed by the tree constructor. For each token the specification defines which DOM element is relevant to it and will be created for this token. Except of adding the element to the DOM tree it is also added to a stack of open elements. This stack is used to correct nesting mismatches and unclosed tags. The algorithm is also described as a state machine. The states are called "insertion modes".

Let's see the tree construction process for the example input:

<html><body>Hello world</body></html>

The input to the tree construction stage is a sequence of tokens from the tokenization stage The first mode is the "initial mode". Receiving the html token will cause a move to the "before html" mode and a reprocessing of the token in that mode. This will cause a creation of the HTMLHtmlElement element and it will be appended to the root Document object.

The state will be changed to "before head". We receive the "body" token. An HTMLHeadElement will be created implicitly although we don't have a "head" token and it will be added to the tree.

We now move to the "in head" mode and then to "after head". The body token is reprocessed, an HTMLBodyElement is created and inserted and the mode is transferred to "in body".

The character tokens of the "Hello world" string are now received. The first one will cause creation and insertion of a "Text" node and the other characters will be appended to that node.

The receiving of the body end token will cause a transfer to "after body" mode. We will now receive the html end tag which will move us to "after after body" mode. Receiving the end of file token will end the parsing.

Figure 10: tree construction of example html

Actions when the parsing is finished

At this stage the browser will mark the document as interactive and start parsing scripts that are in "deferred" mode - those who should be executed after the document is parsed. The document state will be then set to "complete" and a "load" event will be fired.

You can see the full algorithms for tokenization and tree construction in HTML5 specification - http://www.w3.org/TR/html5/syntax.html#html-parser

Browsers error tolerance

You never get an "Invalid Syntax" error on an HTML page. Browsers fix an invalid content and go on.

Take this HTML for example:

<html> <mytag> </mytag> <div> <p> </div> Really lousy HTML </p></html>I must have violated about a million rules ("mytag" is not a standard tag, wrong nesting of the "p" and "div" elements and more) but the browser still shows it correctly and doesn't complain. So a lot of the parser code is fixing the HTML author mistakes.

The error handling is quite consistent in browsers but amazingly enough it's not part of HTML current specification. Like bookmarking and back/forward buttons it's just something that developed in browsers over the years. There are known invalid HTML constructs that repeat themselves in many sites and the browsers try to fix them in a conformant way with other browsers.

The HTML5 specification does define some of these requirements. Webkit summarizes this nicely in the comment at the beginning of the HTML parser class

Let's see some Webkit error tolerance examples:

</br> instead of <br>

Some sites use </br> instead of <br>. In order to be compatible with IE and Firefox Webkit treats this like <br>.

The code:

if (t->isCloseTag(brTag) && m_document->inCompatMode()) { reportError(MalformedBRError); t->beginTag = true;}Note - the error handling is internal - it won't be presented to the user.A stray table

A stray table is a table inside another table contents but not inside a table cell.

Like this example:

<table><table><tr><td>inner table</td></tr> </table><tr><td>outer table</td></tr></table>Webkit will change the hierarchy to two sibling tables:

<table><tr><td>outer table</td></tr></table><table><tr><td>inner table</td></tr> </table>The code:

if (m_inStrayTableContent && localName == tableTag) popBlock(tableTag);Webkit uses a stack for the current element contents - it will pop the inner table out of the outer table stack. The tables will now be siblings.

Nested form elements

In case the user puts a form inside another form, the second form is ignored.

The code:

if (!m_currentFormElement) { m_currentFormElement = new HTMLFormElement(formTag, m_document);}A too deep tag hierarchy

The comment speaks for itself.

www.liceo.edu.mx is an example of a site that achieves a level of nesting of about 1500 tags, all from a bunch of <b>s.We will only allow at most 20 nested tags of the same type before just ignoring them all together.

bool HTMLParser::allowNestedRedundantTag(const AtomicString& tagName){unsigned i = 0;for (HTMLStackElem* curr = m_blockStack; i < cMaxRedundantTagDepth && curr && curr->tagName == tagName; curr = curr->next, i++) { }return i != cMaxRedundantTagDepth;}Misplaced html or body end tags

Again - the comment speaks for itself.

Support for really broken html.We never close the body tag, since some stupid web pages close it before the actual end of the doc.Let's rely on the end() call to close things.

if (t->tagName == htmlTag || t->tagName == bodyTag ) return;So web authors beware - unless you want to appear as an example in a Webkit error tolerance code - write well formed HTML.

CSS parsing

Remember the parsing concepts in the introduction? Well, unlike HTML, CSS is a context free grammar and can be parsed using the types of parsers described in the introduction. In fact the CSS specification defines CSS lexical and syntax grammar (http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/grammar.html).

Let's see some examples:

The lexical grammar (vocabulary) is defined by regular expressions for each token:

comment\/\*[^*]*\*+([^/*][^*]*\*+)*\/num[0-9]+|[0-9]*"."[0-9]+nonascii[\200-\377]nmstart[_a-z]|{nonascii}|{escape}nmchar[_a-z0-9-]|{nonascii}|{escape}name{nmchar}+ident{nmstart}{nmchar}*"ident" is short for identifier, like a class name. "name" is an element id (that is referred by "#" )

The syntax grammar is described in BNF.

ruleset : selector [ ',' S* selector ]* '{' S* declaration [ ';' S* declaration ]* '}' S* ;selector : simple_selector [ combinator selector | S+ [ combinator selector ] ] ;simple_selector : element_name [ HASH | class | attrib | pseudo ]* | [ HASH | class | attrib | pseudo ]+ ;class : '.' IDENT ;element_name : IDENT | '*' ;attrib : '[' S* IDENT S* [ [ '=' | INCLUDES | DASHMATCH ] S* [ IDENT | STRING ] S* ] ']' ;pseudo : ':' [ IDENT | FUNCTION S* [IDENT S*] ')' ] ;Explanation: A ruleset is this structure:div.error , a.error {color:red;font-weight:bold;}div.error and a.error are selectors. The part inside the curly braces contains the rules that are applied by this ruleset. This structure is defined formally in this definition:ruleset : selector [ ',' S* selector ]* '{' S* declaration [ ';' S* declaration ]* '}' S* ;This means a ruleset is a selector or optionally number of selectors separated by a coma and spaces (S stands for white space). A ruleset contains curly braces and inside them a declaration or optionally a number of declarations separated by a semicolon. "declaration" and "selector" will be defined in the following BNF definitions.Webkit CSS parser

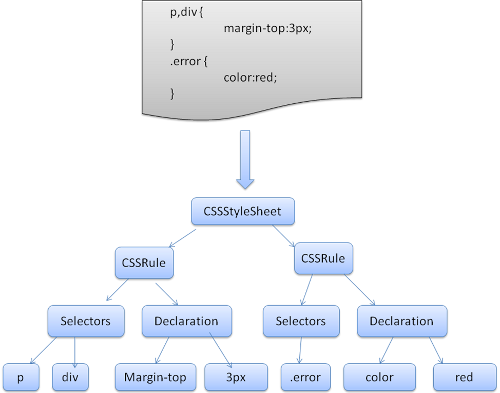

Webkit uses Flex and Bison parser generators to create parsers automatically from the CSS grammar files. As you recall from the parser introduction, Bison creates a bottom up shift reduce parser. Firefox uses a top down parser written manually. In both cases each CSS file is parsed into a StyleSheet object, each object contains CSS rules. The CSS rule objects contain selector and declaration objects and other object corresponding to CSS grammar.

Figure 7: parsing CSS

Parsing scripts

This will be dealt with in the chapter about JavaScriptThe order of processing scripts and style sheets

Scripts

The model of the web is synchronous. Authors expect scripts to be parsed and executed immediately when the parser reaches a <script> tag. The parsing of the document halts until the script was executed. If the script is external then the resource must be first fetched from the network - this is also done synchronously, the parsing halts until the resource is fetched. This was the model for many years and is also specified in HTML 4 and 5 specifications. Authors could mark the script as "defer" and thus it will not halt the document parsing and will execute after it is parsed. HTML5 adds an option to mark the script as asynchronous so it will be parsed and executed by a different thread.

Speculative parsing

Both Webkit and Firefox do this optimization. While executing scripts, another thread parses the rest of the document and finds out what other resources need to be loaded from the network and loads them. These way resources can be loaded on parallel connections and the overall speed is better. Note - the speculative parser doesn't modify the DOM tree and leaves that to the main parser, it only parses references to external resources like external scripts, style sheets and images.

Style sheets

Style sheets on the other hand have a different model. Conceptually it seems that since style sheets don't change the DOM tree, there is no reason to wait for them and stop the document parsing. There is an issue, though, of scripts asking for style information during the document parsing stage. If the style is not loaded and parsed yet, the script will get wrong answers and apparently this caused lots of problems. It seems to be an edge case but is quite common. Firefox blocks all scripts when there is a style sheet that is still being loaded and parsed. Webkit blocks scripts only when they try to access for certain style properties that may be effected by unloaded style sheets.

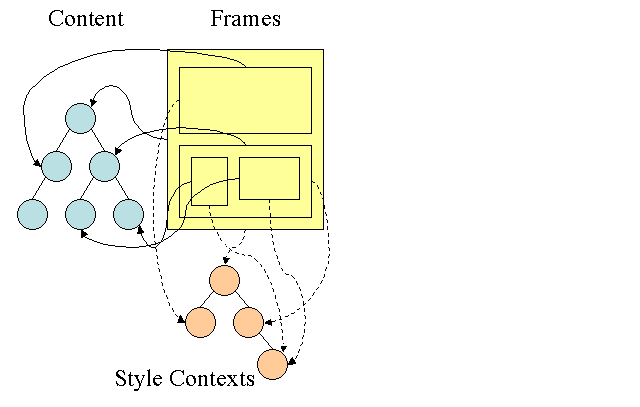

Render tree construction

While the DOM tree is being constructed, the browser constructs another tree, the render tree. This tree is of visual elements in the order in which they will be displayed. It is the visual representation of the document. The purpose of this tree is to enable painting the contents in their correct order.

Firefox calls the elements in the render tree "frames". Webkit uses the term renderer or render object.

A renderer knows how to layout and paint itself and it's children.

Webkits RenderObject class, the base class of the renderers has the following definition:

class RenderObject{virtual void layout();virtual void paint(PaintInfo);virtual void rect repaintRect();Node* node; //the DOM nodeRenderStyle* style; // the computed styleRenderLayer* containgLayer; //the containing z-index layer}Each renderer represents a rectangular area usually corresponding to the node's CSS box, as described by the CSS2 spec. It contains geometric information like width, height and position.

The box type is affected by the "display" style attribute that is relevant for the node (see the style computation section). Here is Webkit code for deciding what type of renderer should be created for a DOM node, according to the display attribute.

RenderObject* RenderObject::createObject(Node* node, RenderStyle* style){ Document* doc = node->document(); RenderArena* arena = doc->renderArena(); ... RenderObject* o = 0; switch (style->display()) { case NONE: break; case INLINE: o = new (arena) RenderInline(node); break; case BLOCK: o = new (arena) RenderBlock(node); break; case INLINE_BLOCK: o = new (arena) RenderBlock(node); break; case LIST_ITEM: o = new (arena) RenderListItem(node); break; ... } return o;}The element type is also considered, for example form controls and tables have special frames. In Webkit if an element wants to create a special renderer it will override the "createRenderer" method. The renderers points to style objects that contains the non geometric information.

The render tree relation to the DOM tree

The renderers correspond to the DOM elements, but the relation is not one to one. Non visual DOM elements will not be inserted in the render tree. An example is the "head" element. Also elements whose display attribute was assigned to "none" will not appear in the tree (elements with "hidden" visibility attribute will appear in the tree).There are DOM elements which correspond to several visual objects. These are usually elements with complex structure that cannot be described by a single rectangle. For example, the "select" element has 3 renderers - one for the display area, one for the drop down list box and one for the button. Also when text is broken into multiple lines because the width is not sufficient for one line, the new lines will be added as extra renderers.

Another example of several renderers is broken HTML. According to CSS spec an inline element must contain either only block element or only inline elements. In case of mixed content, anonymous block renderers will be created to wrap the inline elements.

Some render objects correspond to a DOM node but not in the same place in the tree. Floats and absolutely positioned elements are out of flow, placed in a different place in the tree, and mapped to the real frame. A placeholder frame is where they should have been.

Figure 11: The render tree and the corresponding DOM tree(3.1). The "Viewport" is the initial containing block. In Webkit it will be the "RenderView" object.

The flow of constructing the tree

In Firefox, the presentation is registered as a listener for DOM updates. The presentation delegates frame creation to the "FrameConstructor" and the constructor resolves style(see style computation) and creates a frame.

In Webkit the process of resolving the style and creating a renderer is called "attachment". Every DOM node has an "attach" method. Attachment is synchronous, node insertion to the DOM tree calls the new node "attach" method.

Processing the html and body tags results in the construction of the render tree root. The root render object corresponds to what the CSS spec calls the containing block - the top most block that contains all other blocks. Its dimensions are the viewport - the browser window display area dimensions. Firefox calls it ViewPortFrame and Webkit calls it RenderView. This is the render object that the document point to. The rest of the tree is constructed as a DOM nodes insertion.

See CSS2 on this topic - http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS21/intro.html#processing-model

Style Computation

Building the render tree requires calculating the visual properties of each render object. This is done by calculating the style properties of each element.

The style includes style sheets of various origins, inline style elements and visual properties in the HTML (like the "bgcolor" property).The later is translated to matching CSS style properties.

The origins of style sheets are the browser's default style sheets, the style sheets provided by the page author and user style sheets - these are style sheets provides by the browser user (browsers let you define your favorite style. In Firefox, for instance, this is done by placing a style sheet in the "Firefox Profile" folder).

Style computation brings up a few difficulties:

- Style data is a very large construct, holding the numerous style properties, this can cause memory problems.

- Finding the matching rules for each element can cause performance issues if it's not optimized. Traversing the entire rule list for each element to find matches is a heavy task. Selectors can have complex structure that can cause the matching process to start on a seemingly promising path that is proven to be futile and another path has to be tried.

For example - this compound selector:div div div div{...}Means the rules apply to a "<div>" who is the descendant of 3 divs.Suppose you want to check if the rule applies for a given "<div>" element. You choose a certain path up the tree for checking. You may need to traverse the node tree up just to find out there are only two divs and the rule does not apply. You then need to try other paths in the tree. - Applying the rules involves quite complex cascade rules that define the hierarchy of the rules.

Sharing style data

Webkit nodes references style objects (RenderStyle) These objects can be shared by nodes in some conditions. The nodes are siblings or cousins and:

- The elements must be in the same mouse state (e.g., one can't be in :hover while the other isn't)

- Neither element should have an id

- The tag names should match

- The class attributes should match

- The set of mapped attributes must be identical

- The link states must match

- The focus states must match

- Neither element should be affected by attribute selectors, where affected is defined as having any selector match that uses an attribute selector in any position within the selector at all

- There must be no inline style attribute on the elements

- There must be no sibling selectors in use at all. WebCore simply throws a global switch when any sibling selector is encountered and disables style sharing for the entire document when they are present. This includes the + selector and selectors like :first-child and :last-child.

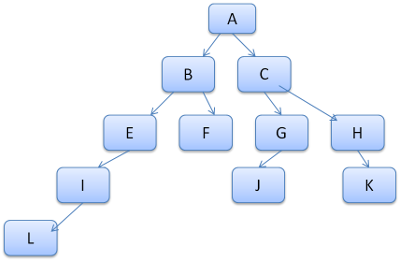

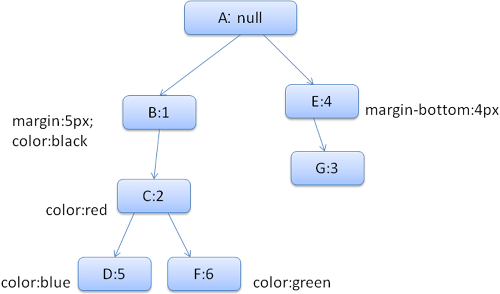

Firefox rule tree

Firefox has two extra trees for easier style computation - the rule tree and style context tree. Webkit also has style objects but they are not stored in a tree like the style context tree, only the DOM node points to its relevant style.

Figure 13: Firefox style context tree(2.2)

The style contexts contain end values. The values are computed by applying all the matching rules in the correct order and performing manipulations that transform them from logical to concrete values. For example - if the logical value is percentage of the screen it will be calculated and transformed to absolute units. The rule tree idea is really clever. It enables sharing these values between nodes to avoid computing them again. This also saves space.

All the matched rules are stored in a tree. The bottom nodes in a path have higher priority. The tree contains all the paths for rule matches that were found. Storing the rules is done lazily. The tree isn't calculated at the beginning for every node, but whenever a node style needs to be computed the computed paths are added to the tree.

The idea is to see the tree paths as words in a lexicon. Lets say we already computed this rule tree:

Let's see how the tree saves as work.

Division into structs

The style contexts are divided into structs. Those structs contain style information for a certain category like border or color. All the properties in a struct are either inherited or non inherited. Inherited properties are properties that unless defined by the element, are inherited from its parent. Non inherited properties (called "reset" properties) use default values if not defined.

The tree helps us by caching entire structs (containing the computed end values) in the tree. The idea is that if the bottom node didn't supply a definition for a struct, a cached struct in an upper node can be used.

Computing the style contexts using the rule tree

When computing the style context for a certain element, we first compute a path in the rule tree or use an existing one. We then begin to apply the rules in the path to fill the structs in our new style context. We start at the bottom node of the path - the one with the highest precedence (usually the most specific selector) and traverse the tree up until our struct is full. If there is no specification for the struct in that rule node, then we can greatly optimize - we go up the tree until we find a node that specifies it fully and simply point to it - that's the best optimization - the entire struct is shared. This saves computation of end values and memory.

If we find partial definitions we go up the tree until the struct is filled.

If we didn't find any definitions for our struct, then in case the struct is an "inherited" type - we point to the struct of our parent in the context tree, in this case we also succeeded in sharing structs. If its a reset struct then default values will be used.

If the most specific node does add values then we need to do some extra calculations for transforming it to actual values. We then cache the result in the tree node so it can be used by children.

In case an element has a sibling or a brother that points to the same tree node then the entire style context can be shared between them.

Lets see an example: Suppose we have this HTML

<html><body><div class="err" id="div1"><p> this is a <span class="big"> big error </span> this is also a <span class="big"> very big error</span> error </p></div><div class="err" id="div2">another error</div> </body></html>And the following rules:

1.div {margin:5px;color:black}2..err {color:red}3..big {margin-top:3px}4.div span {margin-bottom:4px}5.#div1 {color:blue}6.#div 2 {color:green}To simplify things let's say we need to fill out only two structs - the color struct and the margin struct. The color struct contains only one member - the color The margin struct contains the four sides.

The resulting rule tree will look like this (the nodes are marked with the node name : the # of rule they point at):

Figure 12: The rule tree

The context tree will look like this (node name : rule node they point to):

Figure 13: The context tree

Suppose we parse the HTML and get to the second <div> tag. We need to create a style context for this node and fill its style structs.

We will match the rules and discover that the matching rules for the <div> are 1 ,2 and 6. This means there is already an existing path in the tree that our element can use and we just need to add another node to it for rule 6 (node F in the rule tree).

We will create a style context and put it in the context tree. The new style context will point to node F in the rule tree.

We now need to fill the style structs. We will begin by filling out the margin struct. Since the last rule node(F) doesn't add to the margin struct, we can go up the tree until we find a cached struct computed in a previous node insertion and use it. We will find it on node B, which is the uppermost node that specified margin rules.

We do have a definition for the color struct, so we can't use a cached struct. Since color has one attribute we don't need to go up the tree to fill other attributes. We will compute the end value (convert string to RGB etc) and cache the computed struct on this node.

The work on the second <span> element is even easier. We will match the rules and come to the conclusion that it points to rule G, like the previous span. Since we have siblings that point to the same node, we can share the entire style context and just point to the context of the previous span.

For structs that contain rules that are inherited from the parent, caching is done on the context tree (the color property is actually inherited, but Firefox treats it as reset and caches it on the rule tree).

For instance if we added rules for fonts in a paragraph:

p {font-family:Verdana;font size:10px;font-weight:bold} Then the div element, which is a child of the paragraph in the context tree, could have shared the same font struct as his parent. This is if no font rules where specified for the "div".In Webkit, who does not have a rule tree, the matched declarations are traversed 4 times. First non important high priority properties (properties that should be applied first because others depend on them - like display) are applied, than high priority important, then normal priority non important, then normal priority important rules. This means that properties that appear multiple times will be resolved according to the correct cascade order. The last wins.

So to summarize - sharing the style objects(entirely or some of the structs inside them) solves issues 1 and 3. Firefox rule tree also helps in applying the properties in the correct order.

Manipulating the rules for an easy match

There are several sources for style rules:

- CSS rules, either in external style sheets or in style elements.

p {color:blue} - Inline style attributes like

<p style="color:blue" />

- HTML visual attributes (which are mapped to relevant style rules)

<p bgcolor="blue" />

The last two are easily matched to the element since he owns the style attributes and HTML attributes can be mapped using the element as the key.

As noted previously in issue #2, the CSS rule matching can be trickier. To solve the difficulty, the rules are manipulated for easier access.

After parsing the style sheet, the rules are added one of several hash maps, according to the selector. There are maps by id, by class name, by tag name and a general map for anything that doesn't fit into those categories. If the selector is an id, the rule will be added to the id map, if it's a class it will be added to the class map etc.

This manipulation makes it much easier to match rules. There is no need to look in every declaration - we can extract the relevant rules for an element from the maps. This optimization eliminates 95+% of the rules, so that they need not even be considered during the matching process(4.1).

Let's see for example the following style rules:

p.error {color:red}#messageDiv {height:50px}div {margin:5px}The first rule will be inserted into the class map. The second into the id map and the third into the tag map. For the following HTML fragment;

<p class="error">an error occurred </p><div id=" messageDiv">this is a message</div>

We will first try to find rules for the p element. The class map will contain an "error" key under which the rule for "p.error" is found. The div element will have relevant rules in the id map (the key is the id) and the tag map. So the only work left is finding out which of the rules that were extracted by the keys really match.

For example if the rule for the div was

table div {margin:5px}it will still be extracted from the tag map, because the key is the rightmost selector, but it would not match our div element, who does not have a table ancestor.Both Webkit and Firefox do this manipulation.

Applying the rules in the correct cascade order

The style object has properties corresponding to every visual attribute (all css attributes but more generic). If the property is not defined by any of the matched rules - then some properties can be inherited by the parent element style object. Other properties have default values.

The problem begins when there is more than one definition - here comes the cascade order to solve the issue.

Style sheet cascade order

A declaration for a style property can appear in several style sheets, and several times inside a style sheet. This means the order of applying the rules is very important. This is called the "cascade" order. According to CSS2 spec, the cascade order is (from low to high):- Browser declarations

- User normal declarations

- Author normal declarations

- Author important declarations

- User important declarations

The browser declarations are least important and the user overrides the author only if the declaration was marked as important. Declarations with the same order will be sorted by specifity and then the order they are specified. The HTML visual attributes are translated to matching CSS declarations . They are treated as author rules with low priority.

Specifity

The selector specifity is defined by the CSS2 specification as follows:

- count 1 if the declaration is from is a 'style' attribute rather than a rule with a selector, 0 otherwise (= a)

- count the number of ID attributes in the selector (= b)

- count the number of other attributes and pseudo-classes in the selector (= c)

- count the number of element names and pseudo-elements in the selector (= d)

The number base you need to use is defined by the highest count you have in one of the categories.

For example, if a=14 you can use hexadecimal base. In the unlikely case where a=17 you will need a 17 digits number base. The later situation can happen with a selector like this: html body div div p ... (17 tags in your selector.. not very likely).

Some examples:

* {} /* a=0 b=0 c=0 d=0 -> specificity = 0,0,0,0 */ li {} /* a=0 b=0 c=0 d=1 -> specificity = 0,0,0,1 */ li:first-line {} /* a=0 b=0 c=0 d=2 -> specificity = 0,0,0,2 */ ul li {} /* a=0 b=0 c=0 d=2 -> specificity = 0,0,0,2 */ ul ol+li {} /* a=0 b=0 c=0 d=3 -> specificity = 0,0,0,3 */ h1 + *[rel=up]{} /* a=0 b=0 c=1 d=1 -> specificity = 0,0,1,1 */ ul ol li.red {} /* a=0 b=0 c=1 d=3 -> specificity = 0,0,1,3 */ li.red.level {} /* a=0 b=0 c=2 d=1 -> specificity = 0,0,2,1 */ #x34y {} /* a=0 b=1 c=0 d=0 -> specificity = 0,1,0,0 */ style="" /* a=1 b=0 c=0 d=0 -> specificity = 1,0,0,0 */Sorting the rules

After the rules are matched, they are sorted according to the cascade rules. Webkit uses bubble sort for small lists and merge sort for big ones. Webkit implements sorting by overriding the ">" operator for the rules:

static bool operator >(CSSRuleData& r1, CSSRuleData& r2){ int spec1 = r1.selector()->specificity(); int spec2 = r2.selector()->specificity(); return (spec1 == spec2) : r1.position() > r2.position() : spec1 > spec2; }Gradual process

Webkit uses a flag that marks if all top level style sheets (including @imports) have been loaded. If the style is not fully loaded when attaching - place holders are used and it s marked in the document, and they will be recalculated once the style sheets were loaded.

Layout

When the renderer is created and added to the tree, it does not have a position and size. Calculating these values is called layout or reflow.

HTML uses a flow based layout model, meaning that most of the time it is possible to compute the geometry in a single pass. Elements later ``in the flow'' typically do not affect the geometry of elements that are earlier ``in the flow'', so layout can proceed left-to-right, top-to-bottom through the document. There are exceptions - for example, HTML tables may require more than one pass (3.5).

The coordinate system is relative to the root frame. Top and left coordinates are used.

Layout is a recursive process. It begins at the root renderer, which corresponds to the element of the HTML document. Layout continues recursively through some or all of the frame hierarchy, computing geometric information for each renderer that requires it.

The position of the root renderer is 0,0 and its dimensions is the viewport - the visible part of the browser window.All renderers have a "layout" or "reflow" method, each renderer invokes the layout method of its children that need layout.

Dirty bit system

In order not to do a full layout for every small change, browser use a "dirty bit" system. A renderer that is changed or added marks itself and its children as "dirty" - needing layout.

There are two flags - "dirty" and "children are dirty". Children are dirty means that although the renderer itself may be ok, it has at least one child that needs a layout.

Global and incremental layout

Layout can be triggered on the entire render tree - this is "global" layout. This can happen as a result of:

- A global style change that affects all renderers, like a font size change.

- As a result of a screen being resized

Layout can be incremental, only the dirty renderers will be layed out (this can cause some damage which will require extra layouts).

Incremental layout is triggered (asynchronously) when renderers are dirty. For example when new renderers are appended to the render tree after extra content came from the network and was added to the DOM tree.

Figure 20:Incremental layout - only dirty renderers and their children are layed out(3.6).

Asynchronous and Synchronous layout

Incremental layout is done asynchronously. Firefox queues "reflow commands" for incremental layouts and a scheduler triggers batch execution of these commands. Webkit also has a timer that executes an incremental layout - the tree is traversed and "dirty" renderers are layout out.Scripts asking for style information, like "offsightHeight" can trigger incremental layout synchronously.

Global layout will usually be triggered synchronously.

Sometimes layout is triggered as a callback after an initial layout because some attributes , like the scrolling position changed.

Optimizations

When a layout is triggered by a "resize" or a change in the renderer position(and not size), the renders sizes are taken from a cache and not recalculated..In some cases - only a sub tree is modified and layout does not start from the root. This can happen in cases where the change is local and does not affect its surroundings - like text inserted into text fields (otherwise every keystroke would have triggered a layout starting from the root).

The layout process

The layout usually has the following pattern:

- Parent renderer determines its own width.

- Parent goes over children and:

- Place the child renderer (sets its x and y).

- Calls child layout if needed(they are dirty or we are in a global layout or some other reason) - this calculates the child's height.

- Parent uses children accumulative heights and the heights of the margins and paddings to set it own height - this will be used by the parent renderer's parent.

- Sets its dirty bit to false.

Firefox uses a "state" object(nsHTMLReflowState) as a parameter to layout (termed "reflow"). Among others the state includes the parents width.

The output of Firefox layout is a "metrics" object(nsHTMLReflowMetrics). It will contain the renderer computed height.

Width calculation

The renderer's width is calculated using the container block's width , the renderer's style "width" property, the margins and borders.

For example the width of the following div:

<div style="width:30%"/>Would be calculated by Webkit as following(class RenderBox method calcWidth):

- The container width is the maximum of the containers availableWidth and 0. The availableWidth in this case is the contentWidth which is calculated as:

clientWidth() - paddingLeft() - paddingRight()

clientWidth and clientHeight represent the interior of an object excluding border and scrollbar. - The elements width is the "width" style attribute. It will be calculated as an absolute value by computing the percentage of the container width.

- The horizontal borders and paddings are now added.

If the preferred width is higher then the maximum width - the maximum width is used. If it is lower then the minimum width (the smallest unbreakable unit) hen the minimum width is used.

The values are cached, in case a layout is needed but the width does not change.

Line Breaking

When a renderer in the middle of layout decides it needs to break. It stops and propagates to its parent it needs to be broken. The parent will create the extra renderers and calls layout on them.

Painting

In the painting stage, the render tree is traversed and the renderers "paint" method is called to display their content on the screen. Painting uses the UI infrastructure component. More on that in the chapter about the UI.

Global and Incremental

Like layout, painting can also be global - the entire tree is painted - or incremental. In incremental painting, some of the renderers change in a way that does not affect the entire tree. The changed renderer invalidates it's rectangle on the screen. This causes the OS to see it as a "dirty region" and generate a "paint" event. The OS does it cleverly and coalesces several regions into one. In Chrome it is more complicated because the renderer is in a different process then the main process. Chrome simulates the OS behavior to some extent. The presentation listens to these events and delegates the message to the render root. The tree is traversed until the relevant renderer is reached. It will repaint itself (and usually its children).The painting order

CSS2 defines the order of the painting process - http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS21/zindex.html. This is actually the order in which the elements are stacked in the stacking contexts. This order affects painting since the stacks are painted from back to front. The stacking order of a block renderer is:- background color

- background image

- border

- children

- outline

Firefox display list

Firefox goes over the render tree and builds a display list for the painted rectangular. It contains the renderers relevant for the rectangular, in the right painting order (backgrounds of the renderers, then borders etc).That way the tree needs to be traversed only once for a repaint instead of several times - painting all backgrounds, then all images , then all borders etc.

Firefox optimizes the process by not adding elements that will be hidden, like elements completely beneath other opaque elements.

Webkit rectangle storage

Before repainting, webkit saves the old rectangle as a bitmap. It then paints only the delta between the new and old rectangles.Dynamic changes

The browsers try to do the minimal possible actions in response to a change. So changes to an elements color will cause only repaint of the element. Changes to the element position will cause layout and repaint of the element, its children and possibly siblings. Adding a DOM node will cause layout and repaint of the node. Major changes, like increasing font size of the "html" element, will cause invalidation of caches, relyout and repaint of the entire tree.The rendering engine's threads

The rendering engine is single threaded. Almost everything, except network operations, happens in a single thread. In Firefox and safari this is the main thread of the browser. In chrome it's the tab process main thread.Network operations can be performed by several parallel threads. The number of parallel connections is limited (usually 2 - 6 connections. Firefox 3, for example, uses 6).

Event loop

The browser main thread is an event loop. Its an infinite loop that keeps the process alive. It waits for events (like layout and paint events) and processes them. This is Firefox code for the main event loop:while (!mExiting) NS_ProcessNextEvent(thread);

CSS2 visual model

The canvas

According to CCS2 specification, the term canvas describes "the space where the formatting structure is rendered." - where the browser paints the content.

The canvas is infinite for each dimension of the space but browsers choose an initial width based on the dimensions of the viewport.

According to http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/zindex.html, the canvas is transparent if contained within another, and given a browser defined color if it is not.

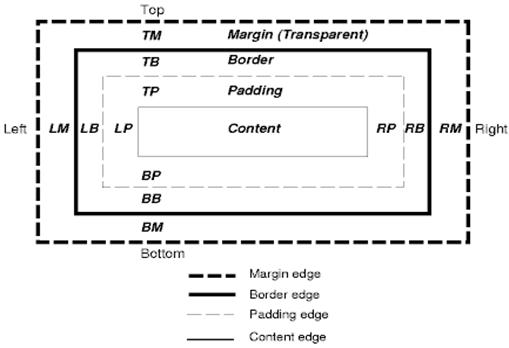

CSS Box model

The CSS box model describes the rectangular boxes that are generated for elements in the document tree and laid out according to the visual formatting model.

Each box has a content area (e.g., text, an image, etc.) and optional surrounding padding, border, and margin areas.

Figure 14:CSS2 box model

Each node generates 0..n such boxes.

All elements have a "display" property that determines their type of box that will be generated.

Examples:

block - generates a block box.inline - generates one or more inline boxes.none - no box is generated.The default is inline but the browser style sheet set other defaults. For example - the default display for "div" element is block.

You can find a default style sheet example here http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/sample.html

Positioning scheme

There are three schemes:

- Normal - the object is positioned according to its place in the document - this means its place in the render tree is like its place in the dom tree and layed out according to its box type and dimensions

- Float - the object is first layed out like normal flow, then moved as far left or right as possible

- Absolute - the object is put in the render tree differently than its place in the DOM tree

The positioning scheme is set by the "position" property and the "float" attribute.

- static and relative cause a normal flow

- absolute and fixed cause an absolute positioning

In static positioning no position is defined and the default positioning is used. In the other schemes, the author specifies the position - top,bottom,left,right.

The way the box is layed out is determined by:

- Box type

- Box dimensions

- Positioning scheme

- External information - like images size and the size of the screen

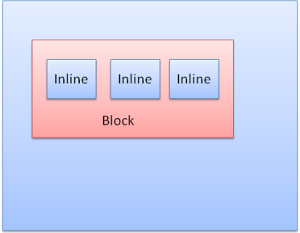

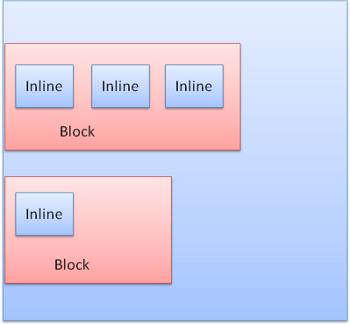

Box types

Block box: forms a block - have their own rectangle on the browser window.

Figure 15:Block box

Inline box: does not have its own block, but is inside a containing block.

Figure 15:Inine boxes

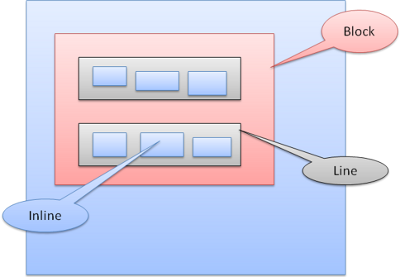

Blocks are formatted vertically one after the other. Inlines are formatted horizontally.

Figure 16:Block and Inline formatting

Inline boxes are put inside lines or "line boxes". The lines are at least as tall as the tallest box but can be taller, when the boxes are aligned "baseline" - meaning the bottom part of an element is aligned at a point of another box other then the bottom. In case the container width is not enough, the inlines will be put in several lines. This is usually what happens in a paragraph.

Figure 17:Lines

Positioning

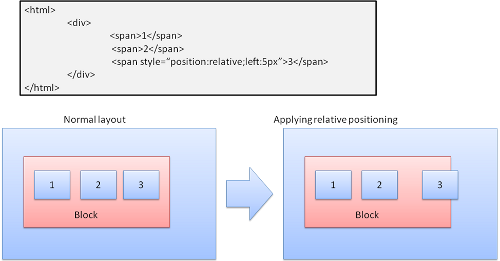

Relative

Relative positioning - positioned like usual and then moved by the required delta.

Figure 18:Relative positioning

Floats

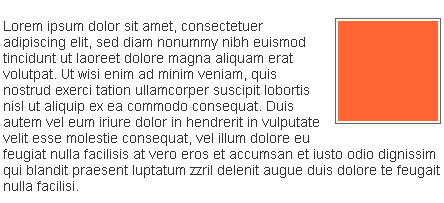

A float box is shifted to the left or right of a line. The interesting feature is that the other boxes flow around it The HTML:

<p><img style="float:right" src="images/image.gif" width="100" height="100">Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer...</p>Will look like:

Figure 19:Float

Absolute and fixed

The layout is defined exactly regardless of the normal flow. The element does not participate in the normal flow. The dimensions are relative to the container. In fixed - the container is the view port.

Figure 20:Fixed positioning

Note - the fixed box will not move even when the document is scrolled!

Layered representation

It is specified by the z-index CSS property. It represents the 3rd dimension of the box, its position along the "z axis".

The boxes are divided to stacks (called stacking contexts). In each stack the back elements will be painted first and the forward elements on top, closer to the user. In case of overlap the will hide the former element.

The stacks are ordered according to the z-index property. Boxes with "z-index" property form a local stack. The viewport has the outer stack.

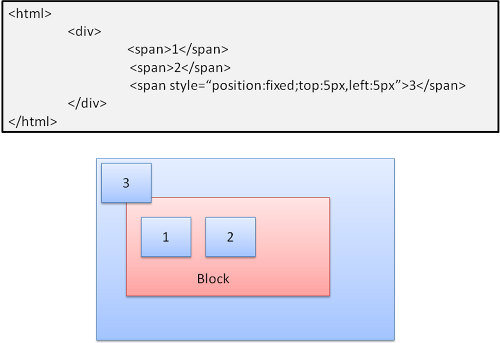

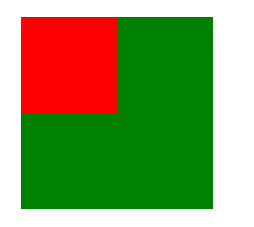

Example:

<STYLE type="text/css"> div { position: absolute; left: 2in; top: 2in; } </STYLE> <P> <DIV style="z-index: 3;background-color:red; width: 1in; height: 1in; "> </DIV> <DIV style="z-index: 1;background-color:green;width: 2in; height: 2in;"> </DIV> </p>The result will be this:

Figure 20:Fixed positioning

Although the green div comes before the red one, and would have been painted before in the regular flow, the z-index property is higher, so it is more forward in the stack held by the root box.

Resources

- Browser architecture

- Grosskurth, Alan. A Reference Architecture for Web Browsers. http://grosskurth.ca/papers/browser-refarch.pdf.

- Parsing

- Aho, Sethi, Ullman, Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools (aka the "Dragon book"), Addison-Wesley, 1986

- Rick Jelliffe. The Bold and the Beautiful: two new drafts for HTML 5. http://broadcast.oreilly.com/2009/05/the-bold-and-the-beautiful-two.html.

- Firefox

- L. David Baron, Faster HTML and CSS: Layout Engine Internals for Web Developers. http://dbaron.org/talks/2008-11-12-faster-html-and-css/slide-6.xhtml.

- L. David Baron, Faster HTML and CSS: Layout Engine Internals for Web Developers(Google tech talk video). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2_6bGNZ7bA.

- L. David Baron, Mozilla's Layout Engine. http://www.mozilla.org/newlayout/doc/layout-2006-07-12/slide-6.xhtml.

- L. David Baron, Mozilla Style System Documentation. http://www.mozilla.org/newlayout/doc/style-system.html.

- Chris Waterson, Notes on HTML Reflow. http://www.mozilla.org/newlayout/doc/reflow.html.

- Chris Waterson, Gecko Overview. http://www.mozilla.org/newlayout/doc/gecko-overview.htm.

- Alexander Larsson, The life of an HTML HTTP request. https://developer.mozilla.org/en/The_life_of_an_HTML_HTTP_request.

- Webkit

- David Hyatt, Implementing CSS(part 1). http://weblogs.mozillazine.org/hyatt/archives/cat_safari.html.

- David Hyatt, An Overview of WebCore. http://weblogs.mozillazine.org/hyatt/WebCore/chapter2.html.

- David Hyatt, WebCore Rendering. http://webkit.org/blog/114/.

- David Hyatt, The FOUC Problem. http://webkit.org/blog/66/the-fouc-problem/.

- W3C Specifications

- HTML 4.01 Specification. http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/.

- HTML5 Specification. http://dev.w3.org/html5/spec/Overview.html.

- Cascading Style Sheets Level 2 Revision 1 (CSS 2.1) Specification. http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/.

- Browsers build instructions

- Firefox. https://developer.mozilla.org/en/Build_Documentation

- Webkit. http://webkit.org/building/build.html

浏览器的工作原理:新式网络浏览器幕后揭秘

一篇一年前的文章,讲的非常细致,说实话,没怎么全看懂,但是可以大体上了解一下里面的内容。文章比较长。因为HTML5 ROCKS网站的css文件好像被墙了,所以决定把这篇文章搬运过来,也算是个存档吧。

那么,下面开始 复制 and 粘贴。(这也是体力活!!!!!!!)

原文地址:http://www.html5rocks.com/zh/tutorials/internals/howbrowserswork/

序言

这是一篇全面介绍 Webkit 和 Gecko 内部操作的入门文章,是以色列开发人员塔利·加希尔大量研究的成果。在过去的几年中,她查阅了所有公开发布的关于浏览器内部机制的数据(请参见资源),并花了很多时间来研读网络浏览器的源代码。她写道:

在 IE 占据 90% 市场份额的年代,我们除了把浏览器当成一个“黑箱”,什么也做不了。但是现在,开放源代码的浏览器拥有了过半的市场份额,因此,是时候来揭开神秘的面纱,一探网络浏览器的内幕了。呃,里面只有数以百万行计的 C++ 代码...

塔利在她的网站上公布了自己的研究成果,但是我们觉得它值得让更多的人来了解,所以我们在此重新整理并公布。

作为一名网络开发人员,学习浏览器的内部工作原理将有助于您作出更明智的决策,并理解那些最佳开发实践的个中缘由。尽管这是一篇相当长的文档,但是我们建议您花些时间来仔细阅读;读完之后,您肯定会觉得所费不虚——保罗·爱丽诗 (Paul Irish),Chrome 浏览器开发人员事务部

简介

网络浏览器很可能是使用最广的软件。在这篇入门文章中,我将会介绍它们的幕后工作原理。我们会了解到,从您在地址栏输入 google.com 直到您在浏览器屏幕上看到 Google 首页的整个过程中都发生了些什么。

我们要讨论的浏览器

目前使用的主流浏览器有五个:Internet Explorer、Firefox、Safari、Chrome 浏览器和 Opera。本文中以开放源代码浏览器为例,即 Firefox、Chrome 浏览器和 Safari(部分开源)。根据 StatCounter 浏览器统计数据,目前(2011 年 8 月)Firefox、Safari 和 Chrome 浏览器的总市场占有率将近 60%。由此可见,如今开放源代码浏览器在浏览器市场中占据了非常坚实的部分。

浏览器的主要功能

浏览器的主要功能就是向服务器发出请求,在浏览器窗口中展示您选择的网络资源。这里所说的资源一般是指 HTML 文档,也可以是 PDF、图片或其他的类型。资源的位置由用户使用 URI(统一资源标示符)指定。

浏览器解释并显示 HTML 文件的方式是在 HTML 和 CSS 规范中指定的。这些规范由网络标准化组织 W3C(万维网联盟)进行维护。 多年以来,各浏览器都没有完全遵从这些规范,同时还在开发自己独有的扩展程序,这给网络开发人员带来了严重的兼容性问题。如今,大多数的浏览器都是或多或少地遵从规范。

浏览器的用户界面有很多彼此相同的元素,其中包括:

用来输入 URI 的地址栏

前进和后退按钮

书签设置选项

用于刷新和停止加载当前文档的刷新和停止按钮

用于返回主页的主页按钮

奇怪的是,浏览器的用户界面并没有任何正式的规范,这是多年来的最佳实践自然发展以及彼此之间相互模仿的结果。HTML5 也没有定义浏览器必须具有的用户界面元素,但列出了一些通用的元素,例如地址栏、状态栏和工具栏等。当然,各浏览器也可以有自己独特的功能,比如 Firefox 的下载管理器。

浏览器的高层结构

浏览器的主要组件为 (1.1):

用户界面 - 包括地址栏、前进/后退按钮、书签菜单等。除了浏览器主窗口显示的您请求的页面外,其他显示的各个部分都属于用户界面。

浏览器引擎 - 在用户界面和呈现引擎之间传送指令。

呈现引擎 - 负责显示请求的内容。如果请求的内容是 HTML,它就负责解析 HTML 和 CSS 内容,并将解析后的内容显示在屏幕上。

网络 - 用于网络调用,比如 HTTP 请求。其接口与平台无关,并为所有平台提供底层实现。

用户界面后端 - 用于绘制基本的窗口小部件,比如组合框和窗口。其公开了与平台无关的通用接口,而在底层使用操作系统的用户界面方法。

JavaScript 解释器。用于解析和执行 JavaScript 代码。

数据存储。这是持久层。浏览器需要在硬盘上保存各种数据,例如 Cookie。新的 HTML 规范 (HTML5) 定义了“网络数据库”,这是一个完整(但是轻便)的浏览器内数据库。

(图:浏览器的主要组件。)

值得注意的是,和大多数浏览器不同,Chrome 浏览器的每个标签页都分别对应一个呈现引擎实例。每个标签页都是一个独立的进程。

呈现引擎

呈现引擎的作用嘛...当然就是“呈现”了,也就是在浏览器的屏幕上显示请求的内容。

默认情况下,呈现引擎可显示 HTML 和 XML 文档与图片。通过插件(或浏览器扩展程序),还可以显示其它类型的内容;例如,使用 PDF 查看器插件就能显示 PDF 文档。但是在本章中,我们将集中介绍其主要用途:显示使用 CSS 格式化的 HTML 内容和图片。

呈现引擎

本文所讨论的浏览器(Firefox、Chrome 浏览器和 Safari)是基于两种呈现引擎构建的。Firefox 使用的是 Gecko,这是 Mozilla 公司“自制”的呈现引擎。而 Safari 和 Chrome 浏览器使用的都是 Webkit。

Webkit 是一种开放源代码呈现引擎,起初用于 Linux 平台,随后由 Apple 公司进行修改,从而支持苹果机和 Windows。有关详情,请参阅 webkit.org。

主流程

呈现引擎一开始会从网络层获取请求文档的内容,内容的大小一般限制在 8000 个块以内。

然后进行如下所示的基本流程:

(图:呈现引擎的基本流程。)

呈现引擎将开始解析 HTML 文档,并将各标记逐个转化成“内容树”上的 DOM 节点。同时也会解析外部 CSS 文件以及样式元素中的样式数据。HTML 中这些带有视觉指令的样式信息将用于创建另一个树结构:呈现树。

呈现树包含多个带有视觉属性(如颜色和尺寸)的矩形。这些矩形的排列顺序就是它们将在屏幕上显示的顺序。

呈现树构建完毕之后,进入“布局”处理阶段,也就是为每个节点分配一个应出现在屏幕上的确切坐标。下一个阶段是绘制 - 呈现引擎会遍历呈现树,由用户界面后端层将每个节点绘制出来。

需要着重指出的是,这是一个渐进的过程。为达到更好的用户体验,呈现引擎会力求尽快将内容显示在屏幕上。它不必等到整个 HTML 文档解析完毕之后,就会开始构建呈现树和设置布局。在不断接收和处理来自网络的其余内容的同时,呈现引擎会将部分内容解析并显示出来。

主流程示例

(图:Webkit 主流程)

(图:Mozilla 的 Gecko 呈现引擎主流程 (3.6))

从图 3 和图 4 可以看出,虽然 Webkit 和 Gecko 使用的术语略有不同,但整体流程是基本相同的。

Gecko 将视觉格式化元素组成的树称为“框架树”。每个元素都是一个框架。Webkit 使用的术语是“呈现树”,它由“呈现对象”组成。对于元素的放置,Webkit 使用的术语是“布局”,而 Gecko 称之为“重排”。对于连接 DOM 节点和可视化信息从而创建呈现树的过程,Webkit 使用的术语是“附加”。有一个细微的非语义差别,就是 Gecko 在 HTML 与 DOM 树之间还有一个称为“内容槽”的层,用于生成 DOM 元素。我们会逐一论述流程中的每一部分:

解析和 DOM 树构建

解析 - 综述

解析是呈现引擎中非常重要的一个环节,因此我们要更深入地讲解。首先,来介绍一下解析。

解析文档是指将文档转化成为有意义的结构,也就是可让代码理解和使用的结构。解析得到的结果通常是代表了文档结构的节点树,它称作解析树或者语法树。

示例 - 解析 2 + 3 - 1 这个表达式,会返回下面的树:

(图:数学表达式树节点)

语法

解析是以文档所遵循的语法规则(编写文档所用的语言或格式)为基础的。所有可以解析的格式都必须对应确定的语法(由词汇和语法规则构成)。这称为与上下文无关的语法。人类语言并不属于这样的语言,因此无法用常规的解析技术进行解析。

解析器和词法分析器的组合

解析的过程可以分成两个子过程:词法分析和语法分析。

词法分析是将输入内容分割成大量标记的过程。标记是语言中的词汇,即构成内容的单位。在人类语言中,它相当于语言字典中的单词。

语法分析是应用语言的语法规则的过程。

解析器通常将解析工作分给以下两个组件来处理:词法分析器(有时也称为标记生成器),负责将输入内容分解成一个个有效标记;而解析器负责根据语言的语法规则分析文档的结构,从而构建解析树。词法分析器知道如何将无关的字符(比如空格和换行符)分离出来。

(图:从源文档到解析树)

解析是一个迭代的过程。通常,解析器会向词法分析器请求一个新标记,并尝试将其与某条语法规则进行匹配。如果发现了匹配规则,解析器会将一个对应于该标记的节点添加到解析树中,然后继续请求下一个标记。

如果没有规则可以匹配,解析器就会将标记存储到内部,并继续请求标记,直至找到可与所有内部存储的标记匹配的规则。如果找不到任何匹配规则,解析器就会引发一个异常。这意味着文档无效,包含语法错误。

翻译

很多时候,解析树还不是最终产品。解析通常是在翻译过程中使用的,而翻译是指将输入文档转换成另一种格式。编译就是这样一个例子。编译器可将源代码编译成机器代码,具体过程是首先将源代码解析成解析树,然后将解析树翻译成机器代码文档。

(图:编译流程)

解析示例

在图 5 中,我们通过一个数学表达式建立了解析树。现在,让我们试着定义一个简单的数学语言,用来演示解析的过程。

词汇:我们用的语言可包含整数、加号和减号。

语法:

构成语言的语法单位是表达式、项和运算符。

我们用的语言可以包含任意数量的表达式。

表达式的定义是:一个“项”接一个“运算符”,然后再接一个“项”。

运算符是加号或减号。

项是一个整数或一个表达式。

让我们分析一下 2 + 3 - 1。

匹配语法规则的第一个子串是 2,而根据第 5 条语法规则,这是一个项。匹配语法规则的第二个子串是 2 + 3,而根据第 3 条规则(一个项接一个运算符,然后再接一个项),这是一个表达式。下一个匹配项已经到了输入的结束。2 + 3 - 1 是一个表达式,因为我们已经知道 2 + 3 是一个项,这样就符合“一个项接一个运算符,然后再接一个项”的规则。2 + + 不与任何规则匹配,因此是无效的输入。

词汇和语法的正式定义

词汇通常用正则表达式表示。

例如,我们的示例语言可以定义如下:

INTEGER :0|[1-9][0-9]*PLUS : +MINUS: -

正如您所看到的,这里用正则表达式给出了整数的定义。

语法通常使用一种称为 BNF 的格式来定义。我们的示例语言可以定义如下:

expression := term operation termoperation := PLUS | MINUSterm := INTEGER | expression

之前我们说过,如果语言的语法是与上下文无关的语法,就可以由常规解析器进行解析。与上下文无关的语法的直观定义就是可以完全用 BNF 格式表达的语法。有关正式定义,请参阅关于与上下文无关的语法的维基百科文章。

解析器类型

有两种基本类型的解析器:自上而下解析器和自下而上解析器。直观地来说,自上而下的解析器从语法的高层结构出发,尝试从中找到匹配的结构。而自下而上的解析器从低层规则出发,将输入内容逐步转化为语法规则,直至满足高层规则。

让我们来看看这两种解析器会如何解析我们的示例:

自上而下的解析器会从高层的规则开始:首先将 2 + 3 标识为一个表达式,然后将 2 + 3 - 1 标识为一个表达式(标识表达式的过程涉及到匹配其他规则,但是起点是最高级别的规则)。

自下而上的解析器将扫描输入内容,找到匹配的规则后,将匹配的输入内容替换成规则。如此继续替换,直到输入内容的结尾。部分匹配的表达式保存在解析器的堆栈中。

堆栈 输入-----------------------------------------2 + 3 - 1项 + 3 - 1项运算 3 - 1表达式 - 1表达式运算符 1表达式

这种自下而上的解析器称为移位归约解析器,因为输入在向右移位(设想有一个指针从输入内容的开头移动到结尾),并且逐渐归约到语法规则上。

自动生成解析器

有一些工具可以帮助您生成解析器,它们称为解析器生成器。您只要向其提供您所用语言的语法(词汇和语法规则),它就会生成相应的解析器。创建解析器需要对解析有深刻理解,而人工创建优化的解析器并不是一件容易的事情,所以解析器生成器是非常实用的。

Webkit 使用了两种非常有名的解析器生成器:用于创建词法分析器的 Flex 以及用于创建解析器的 Bison(您也可能遇到 Lex 和 Yacc 这样的别名)。Flex 的输入是包含标记的正则表达式定义的文件。Bison 的输入是采用 BNF 格式的语言语法规则。

HTML 解析器

HTML 解析器的任务是将 HTML 标记解析成解析树。

HTML 语法定义

HTML 的词汇和语法在 W3C 组织创建的规范中进行了定义。当前的版本是 HTML4,HTML5 正在处理过程中。

非与上下文无关的语法

正如我们在解析过程的简介中已经了解到的,语法可以用 BNF 等格式进行正式定义。

很遗憾,所有的常规解析器都不适用于 HTML(我并不是开玩笑,它们可以用于解析 CSS 和 JavaScript)。HTML 并不能很容易地用解析器所需的与上下文无关的语法来定义。

有一种可以定义 HTML 的正规格式:DTD(Document Type Definition,文档类型定义),但它不是与上下文无关的语法。

这初看起来很奇怪:HTML 和 XML 非常相似。有很多 XML 解析器可以使用。HTML 存在一个 XML 变体 (XHTML),那么有什么大的区别呢?

区别在于 HTML 的处理更为“宽容”,它允许您省略某些隐式添加的标记,有时还能省略一些起始或者结束标记等等。和 XML 严格的语法不同,HTML 整体来看是一种“软性”的语法。

显然,这种看上去细微的差别实际上却带来了巨大的影响。一方面,这是 HTML 如此流行的原因:它能包容您的错误,简化网络开发。另一方面,这使得它很难编写正式的语法。概括地说,HTML 无法很容易地通过常规解析器解析(因为它的语法不是与上下文无关的语法),也无法通过 XML 解析器来解析。

HTML DTD

HTML 的定义采用了 DTD 格式。此格式可用于定义 SGML 族的语言。它包括所有允许使用的元素及其属性和层次结构的定义。如上文所述,HTML DTD 无法构成与上下文无关的语法。

DTD 存在一些变体。严格模式完全遵守 HTML 规范,而其他模式可支持以前的浏览器所使用的标记。这样做的目的是确保向下兼容一些早期版本的内容。最新的严格模式 DTD 可以在这里找到:www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd

DOM

解析器的输出“解析树”是由 DOM 元素和属性节点构成的树结构。DOM 是文档对象模型 (Document Object Model) 的缩写。它是 HTML 文档的对象表示,同时也是外部内容(例如 JavaScript)与 HTML 元素之间的接口。 解析树的根节点是“Document”对象。

DOM 与标记之间几乎是一一对应的关系。比如下面这段标记:

<html><body><p>Hello World</p><div> <img src="example.png"/></div></body></html>

可翻译成如下的 DOM 树:

(图:示例标记的 DOM 树)

和 HTML 一样,DOM 也是由 W3C 组织指定的。请参见 www.w3.org/DOM/DOMTR。这是关于文档操作的通用规范。其中一个特定模块描述针对 HTML 的元素。HTML 的定义可以在这里找到:www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-DOM-Level-2-HTML-20030109/idl-definitions.html。

我所说的树包含 DOM 节点,指的是树是由实现了某个 DOM 接口的元素构成的。浏览器所用的具体实现也会具有一些其他属性,供浏览器在内部使用。

解析算法

我们在之前章节已经说过,HTML 无法用常规的自上而下或自下而上的解析器进行解析。

原因在于:

语言的宽容本质。

浏览器历来对一些常见的无效 HTML 用法采取包容态度。

解析过程需要不断地反复。源内容在解析过程中通常不会改变,但是在 HTML 中,脚本标记如果包含 document.write,就会添加额外的标记,这样解析过程实际上就更改了输入内容。

由于不能使用常规的解析技术,浏览器就创建了自定义的解析器来解析 HTML。

HTML5 规范详细地描述了解析算法。此算法由两个阶段组成:标记化和树构建。

标记化是词法分析过程,将输入内容解析成多个标记。HTML 标记包括起始标记、结束标记、属性名称和属性值。

标记生成器识别标记,传递给树构造器,然后接受下一个字符以识别下一个标记;如此反复直到输入的结束。

(图:HTML 解析流程(摘自 HTML5 规范))

标记化算法

该算法的输出结果是 HTML 标记。该算法使用状态机来表示。每一个状态接收来自输入信息流的一个或多个字符,并根据这些字符更新下一个状态。当前的标记化状态和树结构状态会影响进入下一状态的决定。这意味着,即使接收的字符相同,对于下一个正确的状态也会产生不同的结果,具体取决于当前的状态。该算法相当复杂,无法在此详述,所以我们通过一个简单的示例来帮助大家理解其原理。

基本示例 - 将下面的 HTML 代码标记化:

<html><body>Hello world</body></html>

初始状态是数据状态。遇到字符 < 时,状态更改为“标记打开状态”。接收一个 a-z 字符会创建“起始标记”,状态更改为“标记名称状态”。这个状态会一直保持到接收 > 字符。在此期间接收的每个字符都会附加到新的标记名称上。在本例中,我们创建的标记是 html 标记。

遇到 > 标记时,会发送当前的标记,状态改回“数据状态”。<body> 标记也会进行同样的处理。目前 html 和 body 标记均已发出。现在我们回到“数据状态”。接收到 Hello world 中的 H 字符时,将创建并发送字符标记,直到接收 </body> 中的 <。我们将为 Hello world 中的每个字符都发送一个字符标记。

现在我们回到“标记打开状态”。接收下一个输入字符 / 时,会创建 end tag token 并改为“标记名称状态”。我们会再次保持这个状态,直到接收 >。然后将发送新的标记,并回到“数据状态”。</html> 输入也会进行同样的处理。

(图:对示例输入进行标记化)

树构建算法

在创建解析器的同时,也会创建 Document 对象。在树构建阶段,以 Document 为根节点的 DOM 树也会不断进行修改,向其中添加各种元素。标记生成器发送的每个节点都会由树构建器进行处理。规范中定义了每个标记所对应的 DOM 元素,这些元素会在接收到相应的标记时创建。这些元素不仅会添加到 DOM 树中,还会添加到开放元素的堆栈中。此堆栈用于纠正嵌套错误和处理未关闭的标记。其算法也可以用状态机来描述。这些状态称为“插入模式”。

让我们来看看示例输入的树构建过程:

<html><body>Hello world</body></html>

树构建阶段的输入是一个来自标记化阶段的标记序列。第一个模式是“initial mode”。接收 HTML 标记后转为“before html”模式,并在这个模式下重新处理此标记。这样会创建一个 HTMLHtmlElement 元素,并将其附加到 Document 根对象上。

然后状态将改为“before head”。此时我们接收“body”标记。即使我们的示例中没有“head”标记,系统也会隐式创建一个 HTMLHeadElement,并将其添加到树中。

现在我们进入了“in head”模式,然后转入“after head”模式。系统对 body 标记进行重新处理,创建并插入 HTMLBodyElement,同时模式转变为“body”。

现在,接收由“Hello world”字符串生成的一系列字符标记。接收第一个字符时会创建并插入“Text”节点,而其他字符也将附加到该节点。

接收 body 结束标记会触发“after body”模式。现在我们将接收 HTML 结束标记,然后进入“after after body”模式。接收到文件结束标记后,解析过程就此结束。

(图:示例 HTML 的树构建)

解析结束后的操作

在此阶段,浏览器会将文档标注为交互状态,并开始解析那些处于“deferred”模式的脚本,也就是那些应在文档解析完成后才执行的脚本。然后,文档状态将设置为“完成”,一个“加载”事件将随之触发。

您可以在 HTML5 规范中查看标记化和树构建的完整算法

浏览器的容错机制

您在浏览 HTML 网页时从来不会看到“语法无效”的错误。这是因为浏览器会纠正任何无效内容,然后继续工作。

以下面的 HTML 代码为例:

<html><mytag></mytag><div><p></div>Really lousy HTML</p></html>

在这里,我已经违反了很多语法规则(“mytag”不是标准的标记,“p”和“div”元素之间的嵌套有误等等),但是浏览器仍然会正确地显示这些内容,并且毫无怨言。因为有大量的解析器代码会纠正 HTML 网页作者的错误。

不同浏览器的错误处理机制相当一致,但令人称奇的是,这种机制并不是 HTML 当前规范的一部分。和书签管理以及前进/后退按钮一样,它也是浏览器在多年发展中的产物。很多网站都普遍存在着一些已知的无效 HTML 结构,每一种浏览器都会尝试通过和其他浏览器一样的方式来修复这些无效结构。

HTML5 规范定义了一部分这样的要求。Webkit 在 HTML 解析器类的开头注释中对此做了很好的概括。

解析器对标记化输入内容进行解析,以构建文档树。如果文档的格式正确,就直接进行解析。

遗憾的是,我们不得不处理很多格式错误的 HTML 文档,所以解析器必须具备一定的容错性。

我们至少要能够处理以下错误情况:

明显不能在某些外部标记中添加的元素。在此情况下,我们应该关闭所有标记,直到出现禁止添加的元素,然后再加入该元素。

我们不能直接添加的元素。这很可能是网页作者忘记添加了其中的一些标记(或者其中的标记是可选的)。这些标签可能包括:HTML HEAD BODY TBODY TR TD LI(还有遗漏的吗?)。

向 inline 元素内添加 block 元素。关闭所有 inline 元素,直到出现下一个较高级的 block 元素。