1-objectc-使用对象

来源:互联网 发布:小学记单词软件 编辑:程序博客网 时间:2024/05/22 06:27

原文链接

博客目录链接

使用对象

一个 Objective-C 应用对象的主要工作的结果就是给对象系统发回一个消息。有些对象来自于 Cocoa 或 Cocoa Touch 的实例,有些对象是你自己的类实例。

前一章描述了定义类接口和实现的语法,包括实现返回讯息代码的方法。本章节解释了如何发送此类信息给一个对象,并包含一些 Objective-C 的动态特性,包括动态输入和运行期决定调用方法。

在一个对象可以使用前,必须为它的属性创建合适的内存分配,并对值进行初始化。本章描述了如何构筑方法调用来分配初始化一个对象以确保配置正确。

对象发送和接受消息

在Objective-C中尽管有许多不同的方法在对象间发送消息,但最常用的还是如下的基本语法:

[someObject doSomething];

该例子中左侧符号 someObject 是消息的接收器,消息在右侧,doSomething 是接收器调用函数的方法名。换句话说,当上述代码被执行, someObject 将发送 doSomething 消息。

之前章节描述了如何创建接口,如下:

@interface XYZPerson : NSObject

- (void)sayHello;

@end

以及如何创建接口实现,如下:

@implementation XYZPerson

- (void)sayHello {NSLog(@"Hello, world!");

}

@end

注意: 该例子使用了一个 Objective-C 字符String, @"Hello, world!"。Strings 是 Objective-C 中允许常量快速构建的类中的一个。 指定@"Hello, world!"等同于“一个 Objective-C string 对象代表文字 Hello, world!.”

文本和对象创建的更多信息参见 “Objects Are Created Dynamically,” 本文的稍后部分。

假设你获得一个 XYZPerson 对象,你将发送sayHello 消息如下:

[somePerson sayHello];

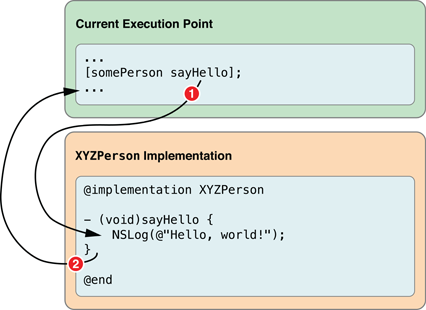

发送一个 Objective-C消息相当于调用一个 C 函数。 Figure 2-1 展示了sayHello 消息的流程。

Figure 2-1 基本消息流程图

为了指定消息接收器,理解指针如何在 Objective-C 中指向对象非常重要。

使用指针保持对象跟踪

C 和 Objective-C 使用变量跟踪值,就像其他编程语言一样。

在标准C中有许多基本数量变量,包括整形、浮点型、字符型,声明和赋值方式如下:

int someInteger = 42;

float someFloatingPointNumber = 3.14f;

局部变量,实在方法或函数中声明的变量,例如:

- (void)myMethod {int someInteger = 42;

}

范围被限制在他们被定义的方法中。

在该例子中, someInteger 被定义为 myMethod 中的局部变量。一旦执行超出方法, someInteger 将不再允许访问。一但局部变量小时,其值也随之消失。

Objective-C 对象,相反的,创建方式有些不同。对象通常比简单的方法调用生命周期更长。特别是当一个对象创建用于跟踪一个原始变量,所以一个对象的内存是动态分配和释放的。

注意:如果你使用过堆 和 栈 的概念,一个局部变量分配在栈上,而对象分配在堆上。

这需要你使用C指针 (保存内存地址)来跟踪他们的内存位置,例如:

- (void)myMethod {NSString *myString = // get a string from somewhere...

[...]

}

尽管指针变量 myString (星号代表它是指针) 的范围被局限在myMethod 范围内,但它指向内存的实际字符对象在该范围外可能有一个更长的生命周期。它可能已经存在,你可能需要通过额外函数调用传递该对象,例如

你可以传递对象为方法参数

如果你需要在发送一个消息时传递一个对象,你提供一个对象指针作为方法的一个参数。前一章描述了声明单个参数方法的语法:

- (void)someMethodWithValue:(SomeType)value;

声明一个带有字符对象的方法的语法如下:

- (void)saySomething:(NSString *)greeting;

你可以实现 saySomething:方法如下:

- (void)saySomething:(NSString *)greeting {NSLog(@"%@", greeting);

}

greeting 指针类似一个局部变量,被限制在saySomething:方法范围内,尽管实际字符串对象产生于函数调用前,并将持续存在到函数调用结束后。

注意:NSLog()使用了替换符指定格式,类似C标准库的printf() 函数。记录到终端中的字符串是格式化字符的结果。

在 Objective-C 中有一个额外的替换符, %@, 用来表示一个对象。在运行时,该说明符将表示调用descriptionWithLocale: 方法(如果存在) 或 description 方法的结果。 The description method is implemented by NSObject to return the class and memory address of the object, but many Cocoa and Cocoa Touch classes override it to provide more useful information. In the case of NSString, the description method simply returns the string of characters that it represents.

For more information about the available format specifiers for use with NSLog() and the NSString class, see “String Format Specifiers”.

Methods Can Return Values

As well as passing values through method parameters, it’s possible for a method to return a value. Each method shown in this chapter so far has a return type of void. The C void keyword means a method doesn’t return anything.

Specifying a return type of int means that the method returns a scalar integer value:

- (int)magicNumber;

The implementation of the method uses a C return statement to indicate the value that should be passed back after the method has finished executing, like this:

- (int)magicNumber {return 42;

}

It’s perfectly acceptable to ignore the fact that a method returns a value. In this case the magicNumber method doesn’t do anything useful other than return a value, but there’s nothing wrong with calling the method like this:

[someObject magicNumber];

If you do need to keep track of the returned value, you can declare a variable and assign it to the result of the method call, like this:

int interestingNumber = [someObject magicNumber];

You can return objects from methods in just the same way. The NSString class, for example, offers an uppercaseString method:

- (NSString *)uppercaseString;

It’s used in the same way as a method returning a scalar value, although you need to use a pointer to keep track of the result:

NSString *testString = @"Hello, world!";

NSString *revisedString = [testString uppercaseString];

When this method call returns, revisedString will point to an NSString object representing the characters HELLO WORLD!.

Remember that when implementing a method to return an object, like this:

- (NSString *)magicString {NSString *stringToReturn = // create an interesting string...

return stringToReturn;

}

the string object continues to exist when it is passed as a return value even though the stringToReturn pointer goes out of scope.

There are some memory management considerations in this situation: a returned object (created on the heap) needs to exist long enough for it to be used by the original caller of the method, but not in perpetuity because that would create a memory leak. For the most part, the Automatic Reference Counting (ARC) feature of the Objective-C compiler takes care of these considerations for you.

Objects Can Send Messages to Themselves

Whenever you’re writing a method implementation, you have access to an important hidden value, self. Conceptually, self is a way to refer to “the object that’s received this message.” It’s a pointer, just like thegreeting value above, and can be used to call a method on the current receiving object.

You might decide to refactor the XYZPerson implementation by modifying the sayHello method to use the saySomething: method shown above, thereby moving the NSLog() call to a separate method. This would mean you could add further methods, like sayGoodbye, that would each call through to the saySomething: method to handle the actual greeting process. If you later wanted to display each greeting in a text field in the user interface, you’d only need to modify the saySomething: method rather than having to go through and adjust each greeting method individually.

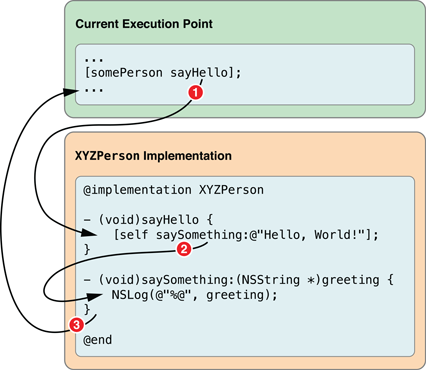

The new implementation using self to call a message on the current object would look like this:

@implementation XYZPerson

- (void)sayHello {[self saySomething:@"Hello, world!"];

}

- (void)saySomething:(NSString *)greeting {NSLog(@"%@", greeting);

}

@end

If you sent an XYZPerson object the sayHello message for this updated implementation, the effective program flow would be as shown in Figure 2-2.

Objects Can Call Methods Implemented by Their Superclasses

There’s another important keyword available to you in Objective-C, called super. Sending a message to super is a way to call through to a method implementation defined by a superclass further up the inheritance chain. The most common use of super is when overriding a method.

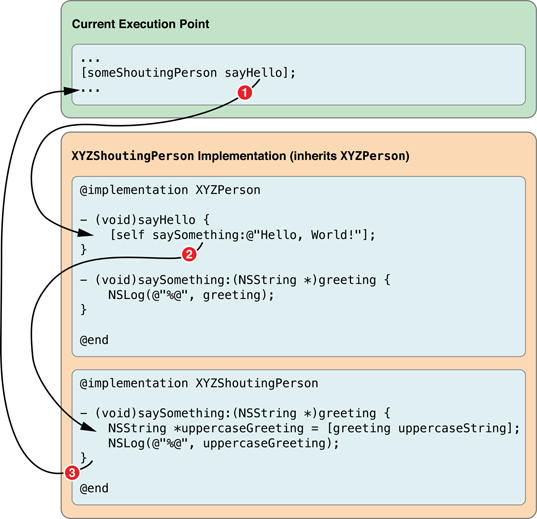

Let’s say you want to create a new type of person class, a “shouting person” class, where every greeting is displayed using capital letters. You could duplicate the entire XYZPerson class and modify each string in each method to be uppercase, but the simplest way would be to create a new class that inherits from XYZPerson, and just override the saySomething: method so that it displays the greeting in uppercase, like this:

@interface XYZShoutingPerson : XYZPerson

@end

@implementation XYZShoutingPerson

- (void)saySomething:(NSString *)greeting {NSString *uppercaseGreeting = [greeting uppercaseString];

NSLog(@"%@", uppercaseGreeting);

}

@end

This example declares an extra string pointer, uppercaseGreeting and assigns it the value returned from sending the original greeting object the uppercaseString message. As you saw earlier, this will be a new string object built by converting each character in the original string to uppercase.

Because sayHello is implemented by XYZPerson, and XYZShoutingPerson is set to inherit from XYZPerson, you can call sayHello on an XYZShoutingPerson object as well. When you call sayHello on anXYZShoutingPerson, the call to [self saySomething:...] will use the overridden implementation and display the greeting as uppercase, resulting in the effective program flow shown in Figure 2-3.

The new implementation isn’t ideal, however, because if you did decide later to modify the XYZPerson implementation of saySomething: to display the greeting in a user interface element rather than throughNSLog(), you’d need to modify the XYZShoutingPerson implementation as well.

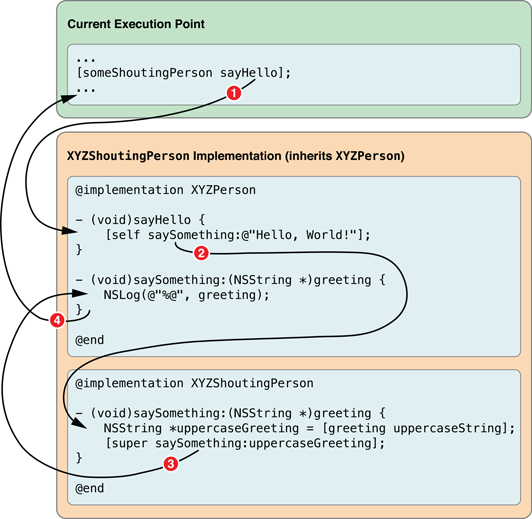

A better idea would be to change the XYZShoutingPerson version of saySomething: to call through to the superclass (XYZPerson) implementation to handle the actual greeting:

@implementation XYZShoutingPerson

- (void)saySomething:(NSString *)greeting {NSString *uppercaseGreeting = [greeting uppercaseString];

[super saySomething:uppercaseGreeting];

}

@end

The effective program flow that now results from sending an XYZShoutingPerson object the sayHello message is shown in Figure 2-4.

Objects Are Created Dynamically

As described earlier in this chapter, memory is allocated dynamically for an Objective-C object. The first step in creating an object is to make sure enough memory is allocated not only for the properties defined by an object’s class, but also the properties defined on each of the superclasses in its inheritance chain.

The NSObject root class provides a class method, alloc, which handles this process for you:

+ (id)alloc;

Notice that the return type of this method is id. This is a special keyword used in Objective-C to mean “some kind of object.” It is a pointer to an object, like (NSObject *), but is special in that it doesn’t use an asterisk. It’s described in more detail later in this chapter, in “Objective-C Is a Dynamic Language.”

The alloc method has one other important task, which is to clear out the memory allocated for the object’s properties by setting them to zero. This avoids the usual problem of memory containing garbage from whatever was stored before, but is not enough to initialize an object completely.

You need to combine a call to alloc with a call to init, another NSObject method:

- (id)init;

The init method is used by a class to make sure its properties have suitable initial values at creation, and is covered in more detail in the next chapter.

Note that init also returns an id.

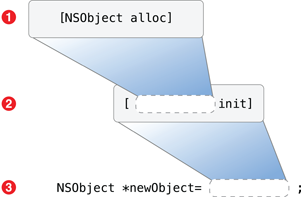

If one method returns an object pointer, it’s possible to nest the call to that method as the receiver in a call to another method, thereby combining multiple message calls in one statement. The correct way to allocate and initialize an object is to nest the alloc call inside the call to init, like this:

NSObject *newObject = [[NSObject alloc] init];

This example sets the newObject variable to point to a newly created NSObject instance.

The innermost call is carried out first, so the NSObject class is sent the alloc method, which returns a newly allocated NSObject instance. This returned object is then used as the receiver of the init message, which itself returns the object back to be assigned to the newObject pointer, as shown in Figure 2-5.

Note: It’s possible for init to return a different object than was created by alloc, so it’s best practice to nest the calls as shown.

Never initialize an object without reassigning any pointer to that object. As an example, don’t do this:

NSObject *someObject = [NSObject alloc];

[someObject init];

init returns some other object, you’ll be left with a pointer to the object that was originally allocated but never initialized.Initializer Methods Can Take Arguments

Some objects need to be initialized with required values. An NSNumber object, for example, must be created with the numeric value it needs to represent.

The NSNumber class defines several initializers, including:

- (id)initWithBool:(BOOL)value;

- (id)initWithFloat:(float)value;

- (id)initWithInt:(int)value;

- (id)initWithLong:(long)value;

Initialization methods with arguments are called in just the same way as plain init methods—an NSNumber object is allocated and initialized like this:

NSNumber *magicNumber = [[NSNumber alloc] initWithInt:42];

Class Factory Methods Are an Alternative to Allocation and Initialization

As mentioned in the previous chapter, a class can also define factory methods. Factory methods offer an alternative to the traditional alloc] init] process, without the need to nest two methods.

The NSNumber class defines several class factory methods to match its initializers, including:

+ (NSNumber *)numberWithBool:(BOOL)value;

+ (NSNumber *)numberWithFloat:(float)value;

+ (NSNumber *)numberWithInt:(int)value;

+ (NSNumber *)numberWithLong:(long)value;

A factory method is used like this:

NSNumber *magicNumber = [NSNumber numberWithInt:42];

This is effectively the same as the previous example using alloc] initWithInt:]. Class factory methods usually just call straight through to alloc and the relevant init method, and are provided for convenience.

Use new to Create an Object If No Arguments Are Needed for Initialization

It’s also possible to create an instance of a class using the new class method. This method is provided by NSObject and doesn’t need to be overridden in your own subclasses.

It’s effectively the same as calling alloc and init with no arguments:

XYZObject *object = [XYZObject new];

// is effectively the same as:

XYZObject *object = [[XYZObject alloc] init];

Literals Offer a Concise Object-Creation Syntax

Some classes allow you to use a more concise, literal syntax to create instances.

You can create an NSString instance, for example, using a special literal notation, like this:

NSString *someString = @"Hello, World!";

This is effectively the same as allocating and initializing an NSString or using one of its class factory methods:

NSString *someString = [NSString stringWithCString:"Hello, World!"

encoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding];

The NSNumber class also allows a variety of literals:

NSNumber *myBOOL = @YES;

NSNumber *myFloat = @3.14f;

NSNumber *myInt = @42;

NSNumber *myLong = @42L;

Again, each of these examples is effectively the same as using the relevant initializer or a class factory method.

You can also create an NSNumber using a boxed expression, like this:

NSNumber *myInt = @(84 / 2);

In this case, the expression is evaluated, and an NSNumber instance created with the result.

Objective-C also supports literals to create immutable NSArray and NSDictionary objects; these are discussed further in “Values and Collections.”

Objective-C Is a Dynamic Language

As mentioned earlier, you need to use a pointer to keep track of an object in memory. Because of Objective-C’s dynamic nature, it doesn’t matter what specific class type you use for that pointer—the correct method will always be called on the relevant object when you send it a message.

The id type defines a generic object pointer. It’s possible to use id when declaring a variable, but you lose compile-time information about the object.

Consider the following code:

id someObject = @"Hello, World!";

[someObject removeAllObjects];

In this case, someObject will point to an NSString instance, but the compiler knows nothing about that instance beyond the fact that it’s some kind of object. The removeAllObjects message is defined by some Cocoa or Cocoa Touch objects (such as NSMutableArray) so the compiler doesn’t complain, even though this code would generate an exception at runtime because an NSString object can’t respond toremoveAllObjects.

Rewriting the code to use a static type:

NSString *someObject = @"Hello, World!";

[someObject removeAllObjects];

means that the compiler will now generate an error because removeAllObjects is not declared in any public NSString interface that it knows about.

Because the class of an object is determined at runtime, it makes no difference what type you assign a variable when creating or working with an instance. To use the XYZPerson and XYZShoutingPerson classes described earlier in this chapter, you might use the following code:

XYZPerson *firstPerson = [[XYZPerson alloc] init];

XYZPerson *secondPerson = [[XYZShoutingPerson alloc] init];

[firstPerson sayHello];

[secondPerson sayHello];

Although both firstPerson and secondPerson are statically typed as XYZPerson objects, secondPerson will point, at runtime, to an XYZShoutingPerson object. When the sayHello method is called on each object, the correct implementations will be used; for secondPerson, this means the XYZShoutingPerson version.

Determining Equality of Objects

If you need to determine whether one object is the same as another object, it’s important to remember that you’re working with pointers.

The standard C equality operator == is used to test equality between the values of two variables, like this:

if (someInteger == 42) {// someInteger has the value 42

}

When dealing with objects, the == operator is used to test whether two separate pointers are pointing to the same object:

if (firstPerson == secondPerson) {// firstPerson is the same object as secondPerson

}

If you need to test whether two objects represent the same data, you need to call a method like isEqual:, available from NSObject:

if ([firstPerson isEqual:secondPerson]) {// firstPerson is identical to secondPerson

}

If you need to compare whether one object represents a greater or lesser value than another object, you can’t use the standard C comparison operators > and <. Instead, the basic Foundation types, like NSNumber,NSString and NSDate, provide a compare: method:

if ([someDate compare:anotherDate] == NSOrderedAscending) {// someDate is earlier than anotherDate

}

Working with nil

It’s always a good idea to initialize scalar variables at the time you declare them, otherwise their initial values will contain garbage from the previous stack contents:

BOOL success = NO;

int magicNumber = 42;

This isn’t necessary for object pointers, because the compiler will automatically set the variable to nil if you don’t specify any other initial value:

XYZPerson *somePerson;

// somePerson is automatically set to nil

A nil value is the safest way to initialize an object pointer if you don’t have another value to use, because it’s perfectly acceptable in Objective-C to send a message to nil. If you do send a message to nil, obviously nothing happens.

Note: If you expect a return value from a message sent to nil, the return value will be nil for object return types, 0 for numeric types, and NO for BOOL types. Returned structures have all members initialized to zero.

If you need to check to make sure an object is not nil (that a variable points to an object in memory), you can either use the standard C inequality operator:

if (somePerson != nil) {// somePerson points to an object

}

or simply supply the variable:

if (somePerson) {// somePerson points to an object

}

If the somePerson variable is nil, its logical value is 0 (false). If it has an address, it’s not zero, so evaluates as true.

Similarly, if you need to check for a nil variable, you can either use the equality operator:

if (somePerson == nil) {// somePerson does not point to an object

}

or just use the C logical negation operator:

if (!somePerson) {// somePerson does not point to an object

}

- 1-objectc-使用对象

- 使用GNU 编译OBjectC

- ObjectC----分类的使用

- 1-objectc-定义类

- flex远程Objectc封装使用

- 【IPHONE开发-OBJECTC入门学习】NSUserDefaults使用

- ObjectC快速入门教程(1)--创建类

- Iphone开发基础篇(二)-ObjectC之面向对象

- Iphone开发基础篇(十)-ObjectC之对象初始化

- 【IPHONE开发-OBJECTC入门学习】复制对象,深浅复制

- 【IPHONE开发-OBJECTC入门学习】对象的归档和解归档

- 【IPHONE开发-OBJECTC入门学习】单例对象设计模式

- [ObjectC]Runtime 运行时之一:类与对象

- 【iOS】swift-ObjectC 在iOS 8中使用UIAlertController

- ObjectC语言基础1—block、protocol、代理设计模式

- objectc 属性

- debug objectc

- IOS开发学习笔记(十一)——ObjectC中集合类型的使用

- androidstudio各版本下载地址

- c#根据字符串创建对象实例

- android api分析19 SQLite

- ewrrewrewrewr

- 运行测试(Running Tests)

- 1-objectc-使用对象

- Linux下解压rar的方法

- CentOs下L2tp+IPsec 配置与相关问题解决

- 关于.net编译过后的程序增加功能的一种实现方式_也可以说是.net exe注入,插件机制_开发记录

- 查看统计信息是否过期

- hibernate中Criteria和DetachedCriteria

- 黑马程序员---java之面向对象(一)

- 如何解决box2DTest中出现的不能运行问题

- 在c++11中你最吃惊的新feature是什么?